Policy

Volatility Is The New Normal In Homebuilding And Development

Beyond a bumpy, choppy, spotty near-term, turbulence seems more and more likely over the longer haul as well.

We’re in the beginning of a downward adjustment in for sale housing. Time will tell if it’s a modest correction, or more severe. Much will depend on the next few months and whether we can sell out the specs in the python (to mix a metaphor) without very large discounts.

That depends on whether demand reduction is gradual, or we hit a buyer air pocket. Also, it ties to whether we greatly reduce spec starts, so that buyers who are in the market need to buy our already under-construction specs.

If the industry believes the demand reduction is modest and temporary, which would normally imply continuing spec starts, but it is more than that, we could create the opposite outcome. If we get very conservative on spec starts, we stand a better chance of avoiding a bigger problem. What’s more, holding back on specs could guarantee a more modest reduction in price.

The downside of an overly conservative spec route is we’d also guarantee a hole in our deliveries in the second and third quarter next year. Tough choice.

This is just an example of the kind of volatility and dilemmas I think we’ll see more, not less, of. The reason is twofold: One, the economy, and the other, the changing nature of our business.

Let’s start with the economic backdrop. We have severe inflation which has both a demand (pumping too much money into the economy) and supply component (supply chain disruptions, war, etc.). The Fed can impact the first by creating a recession (not their goal, but the only likely result if they raise rates enough to actually get inflation back to 2-3%).

The Fed has no impact on the supply side, other than in a negative way. Does anyone believe a recession or even just a reduction in demand will encourage manufacturers to add capacity? Will it encourage oil and gas drillers to invest in long term projects? Will it grow more food? Obviously, NO to all. So, a recession will make the supply side worse in the long run. This goes for housing too.

Resiliency Has Its Price

The reality is, we’re transitioning the global economy to something more regional – whether that’s on-shoring, friend-shoring, etc. And that will take time. As we painfully keep finding out, when we alter supply chains, we’re a single $5-part away from big delays. And it is also inherently inflationary. Being resilient has lots of advantages. The lowest cost is not one of them.

Energy is the most significant transition of our lifetime and there is an enormous tension between having enough fossil fuels now – which requires investment that is predicated on a belief in long-run demand – and efforts to combat climate change, all aimed at creating the demise of that which we need more of now. It seems unlikely we’ll find the right balance here without a number of inevitable periodic energy shocks.

Housing is transitioning too. While a few markets like California have been supply-constrained for decades, for most, this is the first cycle where it seemed impossible to bring on enough supply of lots to meet demand – even given some time. While there is much discussion about housing across the country, there is no region that has developed a housing problem that has put forth a credible plan to truly reverse or even stabilize it.

While it would be great to believe this will happen, experience and actions say not.

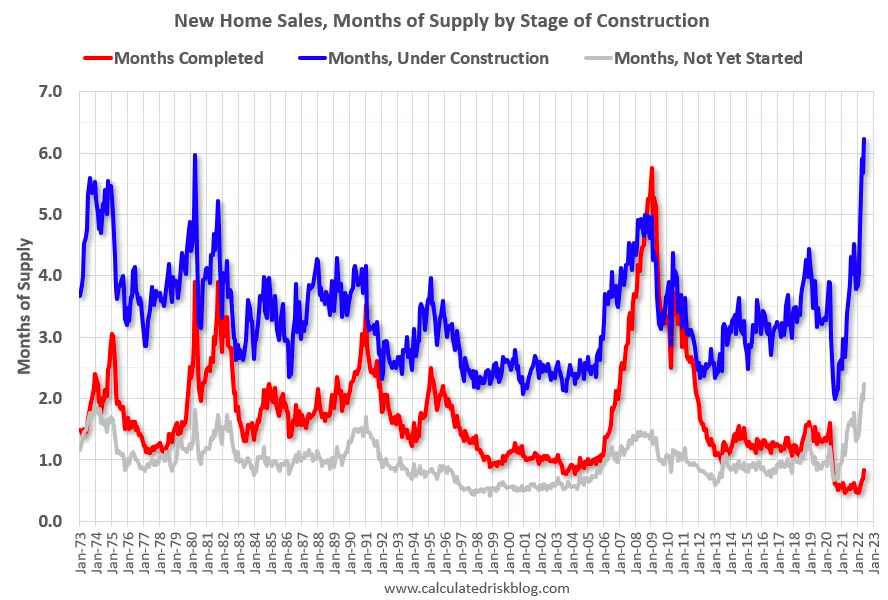

To be clear, long-run demand shortages do not rule out short term oversupplies. In fact, it almost guarantees it. When entitlements take years; when simply getting from a tentative to a final plat starts to feel like a discretionary unpredictable process, the time to react to demand can easily be 3-5 years (or more).

Once demand starts to rise, there is no way to meet it with sufficient supply increase. Rising prices sway more people to buy now rather than later, and the cycle commences. As prices and absorption rates rise, projects that were not previously feasible, land asking prices that could not be met, remote locations with insufficient price differential, all begin to work. And so, supply slowly, grindingly, begins to come forward.

Problem is, supply arrives too late to stem prices over-shooting or running into the next recession. And so, another cycle plays out.

None of this is entirely new, but it is getting amplified. If you pair a fragile economy that seems to require more and more debt/stimulus to grow with a broken housing supply process, you’ll get more volatility in housing markets. It’s tough to be in a business that requires you to buy inventory years in advance, especially when our sales volumes fluctuate far more than most industries through a full cycle.

So, what to do? Neither land development, nor home building has easy options. Land development is a relatively overhead-light business, which helps it, but the timeframes tend to run so long that an honest pro forma would likely always come with a recession baked into it. Good luck explaining that (says the recovering private equity investor). Homebuilding is cursed both with buying land out in front and overhead that does not evenly scale. Shrinking a homebuilder and not having G&A eat any profits alive is – if not impossible – close to it.

Will Build-To-Rent Remain Counter-Cyclical?

It’s possible that selling to investors will be a lifeline this time around, although I’m not sure it is as easy as it sounds in many situations. At the very least, it’s not something to count on as a get-out-of-jail-free card.

Building up build-to-rent as a consistent part of our business may help create more constant volumes for us in the future, although it’s likely that part of the business will become cyclical as well. Can we count on it to be counter-cyclical to for-sale in the future? That’s an argument being made now, but it will probably take another cycle to know for sure.

One of the things that separate homebuilding from much of real estate is how much homebuilding firms do “in-house.” Sales and marketing (with a few exceptions) and construction in particular. Small- and regional sized home builders would be greatly helped if off-site building really took off. Or better yet, if true turn-key GCs for homebuilding became widely available. And being the GC ripples through the rest of the organization. Directly managing so many trades impacts not just the need for a purchasing department and depth in construction management and field work, but also increases the demands on accounting and finance, tracking all of it.

So, a true GC option for builders would exert a material impact on the base level of overhead needed. For starters it would make it a bit easier to manage erratic volumes. Perhaps as more single-family build-for-rent looks for a GC solution in homebuilding, it will be the catalyst for an alternative similar to other parts of real estate and construction.

But, with a few exceptions, we’re not there yet.

Cycle Timing

Which takes us to capital. It’s awfully difficult to have perfect timing of cycles. But one can decide to ratchet risk up and down, and part of doing that is how your company/projects are capitalized. There is no magic to share risk and not profits, so the trade-off is always there. But staying in business is a good start on making money in the long run. Yes, I know, too late at this point to change capitalization.

And for private builders, their public builder competition has de-levered to the point they could survive nearly anything.

Right now, we have to make the hard decisions on betting on growth and starting that new project or buying the next group of lots, or becoming cautious and accepting the hole in our pipelines/deliveries. Those who bet big in April of 2020 that COVID-19 would not crush the housing market made a gutsy call that paid off.

Will it again? I’m not sure the situation today is quite the same. It’s unclear whether and when the Fed or Federal government will turn on the money hose. And that would not fix our affordability issues. Time will tell, and frustratingly, the more conservative we all are, the more we increase the odds of avoiding severe issues.

Prisoner’s dilemma.

As we plan for the long run future, I think we should expect more volatility in our markets, which means more risk that has to be managed to survive and prosper.

Join the conversation

MORE IN Policy

Texas Treads A New Path Into Zoning To Battle Housing Crisis

Texas is one of the nation's most active homebuilding states, yet affordability slips out of reach for millions. Lawmakers now aim to rewire the state’s zoning laws to boost supply, speed up approvals, and limit local obstruction. We unpack three key bills and the stakes behind them.

Together On Fixing Housing: Solve Two, Start the Rest

NAHB Chief Economist Robert Dietz and Lennar Mortgage President Laura Escobar argue that the housing crisis won’t be solved by magic. It starts with a unified focus on two or three priorities—a rallying cry for builders, developers, lenders, and policy-makers.

Zone Offense: North Carolina Moves To Fast-Track By Right Housing

North Carolina legislators are pushing a bipartisan bill that could fast-track housing where people need it most: near jobs and transit. Richard Lawson breaks down what it means, how it compares to other states’ moves, and why developers are watching closely.