Capital

Two Bleak Realities And The Glow Of Their Opportunity In Housing

Housing -- especially in the 'starter' spectrum -- is a shrinking universe. Incomes -- at the low- to mid-level -- have lost pace. Now, what to do about it.

To-do lists are the bane of many a leader. There are always too many to-dos. One multifamily strategist we know described his handling of the dilemma.

"For every 100 most important things I have to do each day, I whittle it down to 10 and then cut that number in half."

It's the realist's approach to chiseling to priorities. And it's culturally where leadership in housing, both for profit-making interest and a community-wide business upside, finds itself in the throes of opportunity.

Here are two sobering matters that directly and ever-more-intensely challenge people, firms, industry sectors, and the economy.

- Entry-level homeownership's "zone" of inclusion among American households – a touchstone of the American Dream of merit-based mobility – is at risk of shrinking beyond recognition to a privileged few.

- Middle-income wage earners have not reaped the benefits of five decades of productivity gains, effectively neutralizing another key force factor in attainability and access to market-rate housing development and construction.

Let's look at evidence in recent reporting.

Last week, National Association of Home Builders assistant VP for survey research Rose Quint noted here:

Housing affordability weakened slightly during the first quarter of 2021 as rising material costs and supply shortages, along with expected increases in mortgage rates stemming from a growing economy, are likely to exacerbate affordability challenges in the year ahead.

According to the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB)/Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index (HOI), 63.1 percent of new and existing homes sold between the beginning of January and end of March were affordable to families earning the U.S. median income of $79,900. This is slightly down from the 63.3 percent of homes sold in the fourth quarter of 2020 that were affordable to households earning the median income of $78,500.

Still, that data masks a starker, more material disparity in and among the households who can participate in today's hyperbolic housing market, versus those who can't even think about doing so.

The Wall Street Journal's Ben Eisen, reported in "Housing-Market Surge Is Making The Cheapest Homes The Hottest," that beneficiaries of the red-hot market and submarket housing activity may not be the ones who actually live where house prices are low.

While prices in many low-cost areas remain far below national averages, some worry that the price appreciation either won’t last or won’t reach the residents who stand to benefit most. The rising prices could also lock some families out of homeownership, especially young people and first-time buyers.

It is unclear if the recent rise “is a sign of upward and sustainable wealth accumulation for low-income and minority households,” said Karen Petrou, author of “Engine of Inequality: The Fed and the Future of Wealth in America.” “I think the data is at best equivocal on that point.”

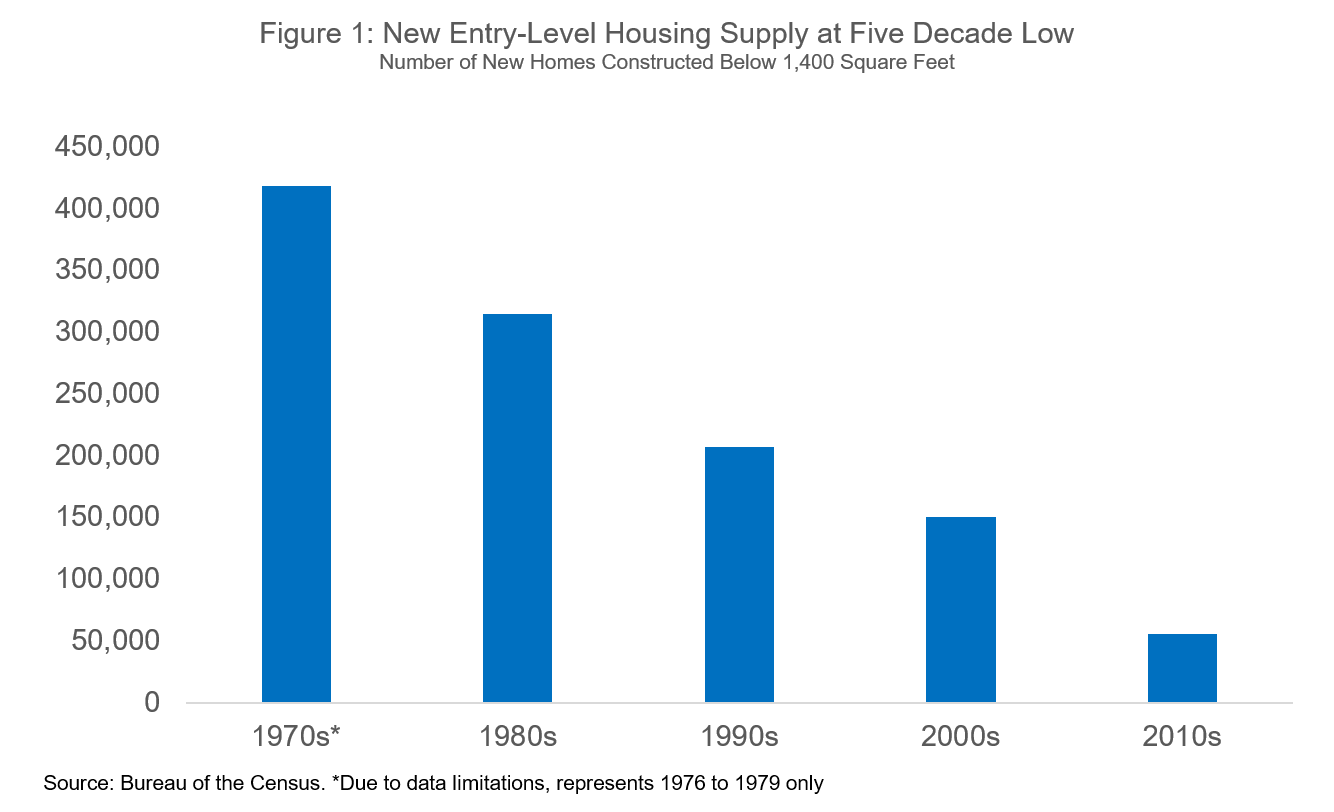

The picture really becomes grim as you look through a lens on one of the bastions of the American Dream of homeownership: the starter home. Freddie Mac chief economist and VP of Economic and Housing Research Sam Khater spotlights the entry-level home production choke-point in a brief analysis here:

While in 2020 only 65,000 entry-level homes were completed, there were 2.38 million first-time homebuyers that purchased homes. Not all renters looking to purchase their first home were in the market for entry-level homes, however the large disparity illustrates the significant and rapidly widening gap between entry-level supply and demand.

As we navigate our way through the year and get beyond the pandemic, we expect the housing supply shortage to continue to be one of the largest obstacles to inclusive economic growth in the U.S. Simply put, we must build more single-family entry-level housing to address this shortage, which has strong implications for the wealth, health and stability of American communities.

The angst most people in housing bring to this issue focuses primarily on prices, and ideas, challenges, and opportunities to "bend the cost curve" to lower price hurdles. This would, if it worked, pry open that shrinking box of access to participation among lower-earning households.

At the same time, too few of the ideas, challenges, and commitments to solutions focus on the promise and possibility of "bending the payment power curve," i.e. raising incomes among more wage earners in such a way that would enable them to come out on to the market-rate housing dance floor.

A New York Times analysis from Noam Sheiber suggests that policy – which accounts for at least part of the reason household wages among mid-income earners have fallen behind over the past several economic cycles – may play a role in expanding the universe of potential buyer prospects for starter homes.

“There is just an increasing body of work trying to quantify both the direct and indirect effects of declining worker bargaining power,” said Anna Stansbury, the co-author of a well-received paper on the subject with former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers. After receiving her doctorate, she will join the faculty of the M.I.T. Sloan School of Management this fall.

“Whether it explains three-quarters or one-half” of the slowdown in wage growth, she continued, “for me the evidence is very compelling that it’s a nontrivial amount.”

Lowering costs is only part of the solution. Raising incomes – payment power – in large part by reigniting belief in an equity-based American Dream that ties effort, agency, and achievement, is an equally important part of the equation.