Land

Superstar Cities Vs. Zoom Towns: Flyover Country Magnetism

Two iconic geographers, Richard Florida and Joel Kotkin, unveil a take on a new geography of post-pandemic live-work balance.

A no-huddle offense approach to learning to live and work, start households and procreate, produce and consume comes clear in the construct of the present being the onset of post-pandemic life as we know it.

For real estate investors, the moment is daunting, not just for how obscure particular fundamental dimensions of the space – residential, commercial office and retail, institutional, industrial – have become.

The added tension for those investors, of course, is the heaps and heaps of global capital thirsting for yield, precisely as signals of certain forces of inflation enter a red zone, tripping alarm.

What would your lightning-round, one-word responses be to the following questions, for example?

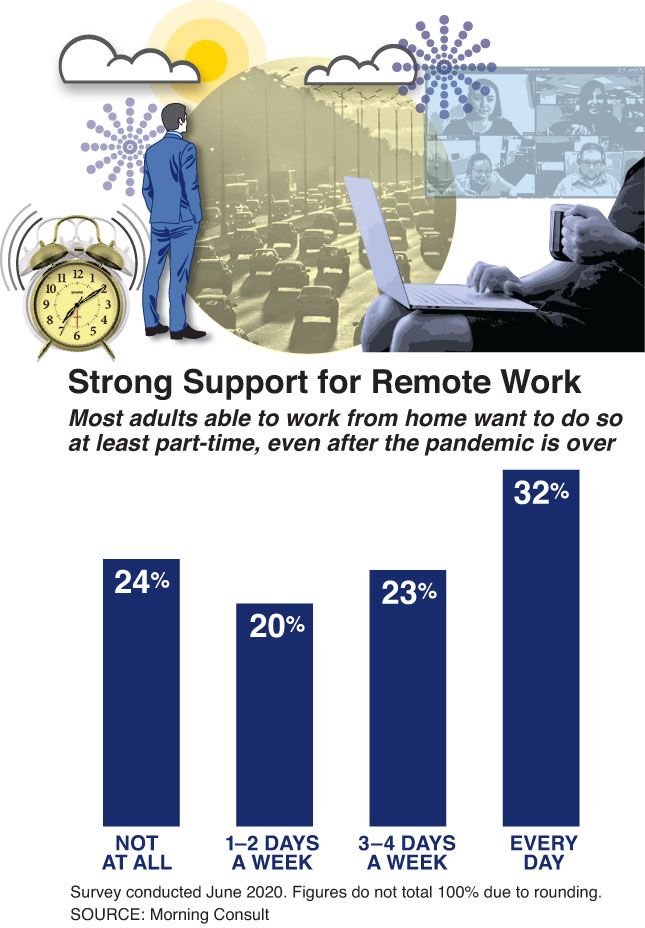

- Fad or trend: Work from anywhere?

- True or false: Sticks and bricks retail's death-knell has sounded?

- Head-fake or pivot: Commuting to job center hub offices will never be the same?

- Fact or fantasy: Suburban mega-malls will be residential-centric footprints?

Fortunately for us, a refreshingly common ground vision that real estate investors, developers, builders, and their partners will do well to explore has been put forward by two master geographers of our era: Richard Florida, a professor at the University of Toronto, and Joel Kotkin, a fellow at Chapman University and executive director of the Urban Reform Institute. Both are senior fellows at Heartland Forward.

Florida and Kotkin's City Journal analysis, America’s Post-Pandemic Geography, attributes a silver-lining potential impact of the pandemic, accelerating already-evident "re-balancing" and dispersion of much-too-concentrated energies and talent for innovation. They write:

A new model appears to be emerging, transforming many suburbs from bedroom communities to mixed-use places: Bethesda, Maryland; Birmingham, Michigan; Orange, California; and Coral Gables, Florida—all boast walkable downtowns and amenities similar to those found in larger cities. Places like Fairfax, Virginia, the Woodlands and Cinco Ranch outside Houston, and Irvine, California, are shifting toward this more mixed-use development model. Remote work gives such suburbs a chance to remake themselves into places where people work closer to where they live. One of the biggest trends we see in the offing is a shift of offices back to suburbs; abandoned malls and office parks can be transformed into new remote work hubs with office space, coworking space, restaurants, cafés, and fitness studios, as well as single-family homes, town homes, and rental apartments.

All but written off before the pandemic, rural America is now having a moment of its own. Story after story has chronicled the movement of affluent urbanites to vacation retreats like the Hudson Valley, Santa Barbara, the Napa Valley, and the skiing paradises of Colorado, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and Idaho—or to so-called Zoom towns. Rural gentrification is not new. Most locales on the short list of up-and-coming rural places have been on the upswing for a while. Remote work simply made it possible for some affluent people to live full-time in their vacation and second homes and for other newly remote workers to leapfrog the suburbs and move farther out.

One of Florida's and Kotkin's more intriguing geographical brainstorms here shares figurative relevance with a notion that enjoys currency among climate, sustainability, and net carbon positive narratives: The handprint versus the footprint. Handprints being more intentional, more mindful, more accountable in the construct, while footprints refer to impacts that are heavier, more consequential in a negative sense.

As they peer around the dimmed corners of the present, Florida and Kotkin see a similar macro trend developing in the area of livelihood, job centers, and household income:

As companies reduce their physical footprints, the driving force of local economic development shifts from attracting businesses to attracting and retaining talent.

The third-rail theme running through these experts' analysis conveys a truly futuristic take, not only on forces in play prior to Covid's shock-and-awe arrival last year, but given an order of magnitude bump up in velocity since.

And, make no mistake, this complicates matters for investors in real estate across the spectrum of residential, commercial office, retail, and hospitality, institutional, and industrial, because, well, here it is:

Cities can become as much about living as about working, not just places where we compromise life and family for economic gain. Suburbs can become more about working, not just about safer and more comfortable living. Parts of rural America, now connected to the wider world by wireless communications and filled with more remote workers, can build more robust economies. The move of immigrants and millennials to these areas will change them economically as well as culturally.

None of this will magically snap into being but will require intentional and strategic action. Without it, the socioeconomic and geographic inequities that have come to define American life will only grow. What comes next can be better—but only if we make it so.

In this construct, housing can be, must be, and is a solution in and of itself. That should be both affirming to its established stakeholders, and hugely challenging.

Join the conversation