Policy

Housing Solutions-Seekers Put Racial Inequity In The Crosshairs

Housing's tale of two realities, White and Black, collided full-force a year ago with health, economic, and social-justice upheavals. Leaders must address this triplex of crises wholly.

Housing's tale of two realities – White and Black – collided full-force a year ago with health, economic and social-justice upheavals.

Housing leaders' challenge – and opportunity – would be to address this three-headed monster of crises wholly. And what better time could there be than now? As the early aftermath and learning-to-live-with-COVID-19 early 2020s turn the screws tighter and more destructively on vulnerable populations, commitment, action and improvement are urgently in order.

Especially, as those who've been spared the most grief recover faster.

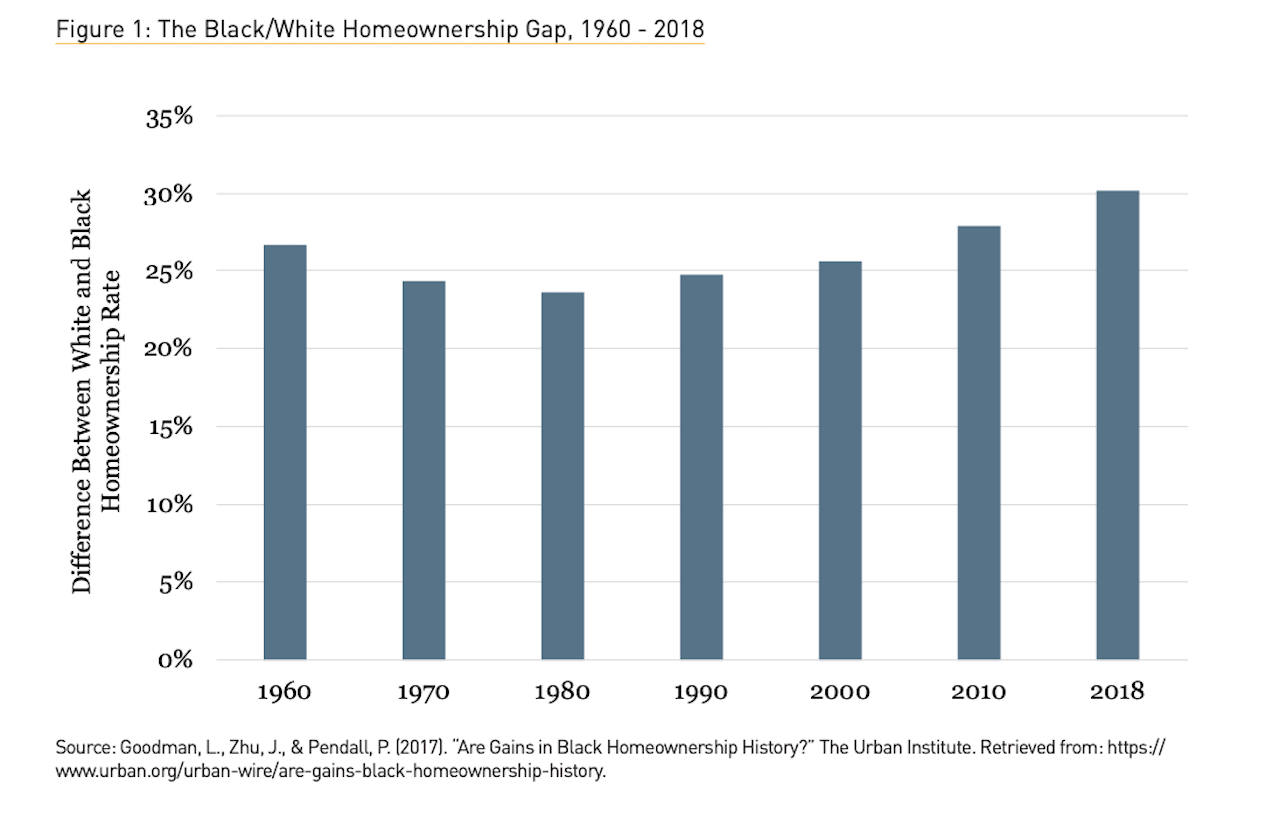

First off, there's a 30% gap in rates of homeownership among white adults versus Blacks.

The disparity masks multitudes of other measures of inequality. And, in the wake of COVID-19, the statistics in turn mask a human story of a housing system hardwired to give people of color less access to shelter, narrower pathways to equity, and a tougher set of pre-existing financial and social conditions that work as recurrent, self-fulfilling-prophecy barriers to attaining places in communities where they can flourish.

The challenge mirrors that profound disequilibrium in the bulwarks of American society. It's structural. And it's historically set. Many accept these "norms" as received wisdom; they work the way they do because they need to work that way.

Black Americans are often unable to build wealth from homeownership in the same way their white peers are, in large part because home prices are generally set by the people who make up the majority of buyers: white Americans. White families typically prefer to live in predominantly white neighborhoods with very few or no Black neighbors. Homes in these neighborhoods tend to have the highest market values because most prospective purchasers — who happen to be white — find them most desirable.

Black Americans, on the other hand, tend to prefer to live in racially diverse or all-Black neighborhoods. Research has shown that once more than 10 percent of your neighbors are Black, the value of your home declines. As the percentage of Black neighbors increases, the property’s value plummets even further.

Housing policy – including taxation – and finance, from their deep roots to their present-day role in determining outcomes of who lives where and how much each place is worth, need to dismantle racist practices up and down housing's value chain.

The excerpt above, from Dorothy A. Brown, Emory University professor of law and author, appeared in a New York Times opinion piece, "Your Home's Value Is Based on Racism."

Dorothy Brown's analysis speaks to a vicious circle of human-imposed conditions, rules of engagement, tax laws, policies, and practices. Together, they impact both property values and appreciation rates that equate, as it works in the real world, to siphoning off value from low-income homeowners and apportioning greater benefits – in tax savings and home appreciation – to higher-income white property owners.

The model determines that, by and large, people of color start with less equity and progressively have fewer paths to equity growth.

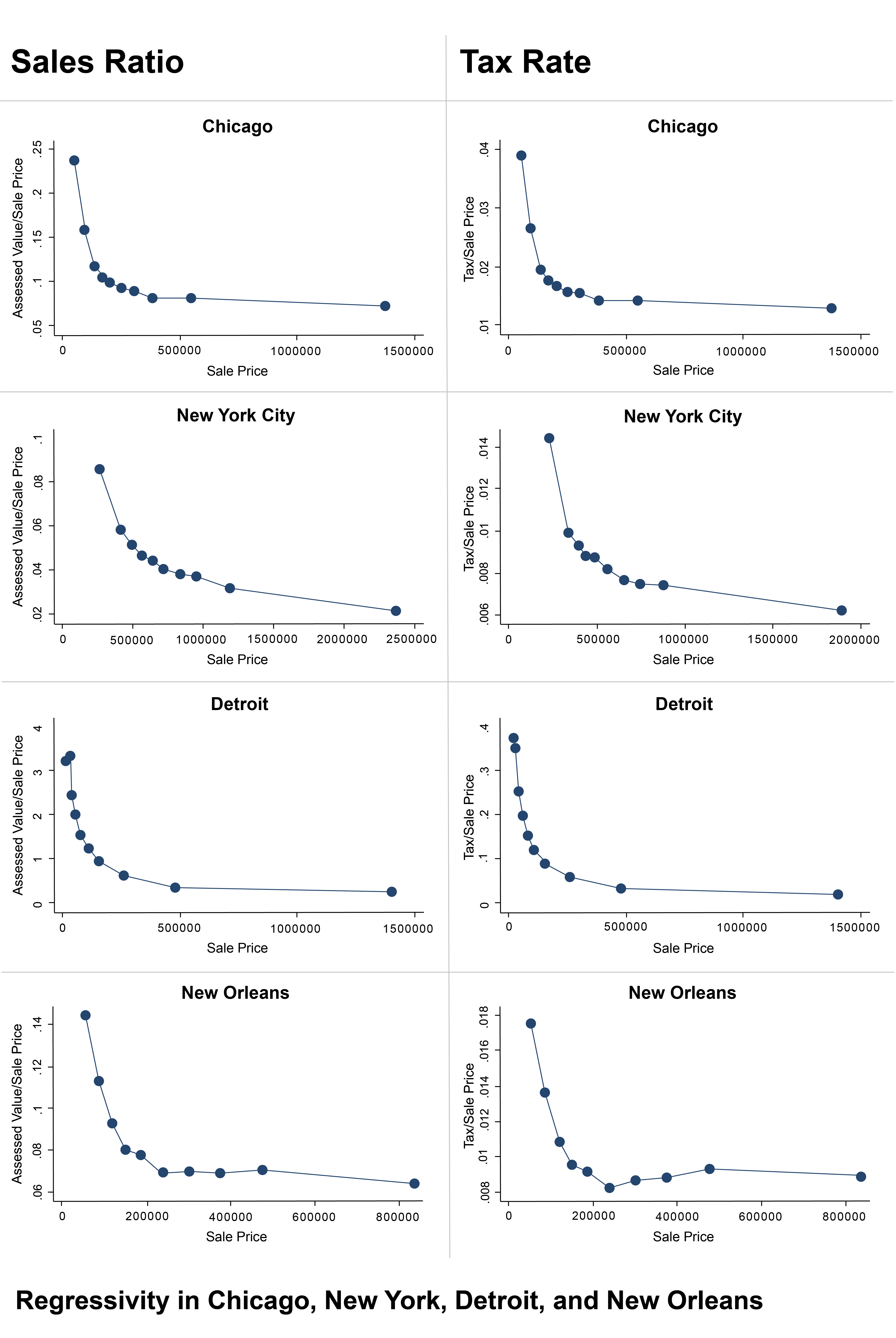

A new nationwide analysis led by Christopher Berry of the University of Chicago reveals that the inequities in tax assessments are both very large and very common.

As the New York Times points out, people with low-valued home properties carry what works out to be double the local property tax burden of people with higher-valued homes in the same metro area.

The burden falls disproportionately on minorities. Because of the accumulated effects of past racism, minorities tend to live in homes that command lower prices — yet are assessed at inflated values.

The data evidence of this social and financial "rigging" comes through as well in a separate study, one researched by Carlos Avenancio-León, of Indiana University, Bloomington and Troup Howard, the University of California, Berkeley for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

The math proves out that what's taken to be a fair, flat, equitable formula for assessing property taxes actually fundamentally disadvantages minority community members.

[We] use panel data covering 118 million homes in the United States, merged with geolocation detail for 75,000 taxing entities, to document a nationwide “assessment gap” which leads local governments to place a disproportionate fiscal burden on racial and ethnic minorities. We show that holding jurisdictions and property tax rates fixed, black and Hispanic residents nonetheless face a 10–13% higher tax burden for the same bundle of public services. This assessment gap arises through two channels. First, property assessments are less sensitive to neighborhood attributes than market prices are. This generates racially correlated spatial variation in tax burden within jurisdiction. Second, appeals behavior and appeals outcomes differ by race. This results in higher assessment growth rates for minority residents.

These systems, models, accepted practices, and policies have gained stature and acceptance over scores of years as norms. A Terner Center for Housing Innovation at U.C. Berkeley analysis from faculty research advisor Carolina K. Reid notes:

Anti-Black racism persists throughout the continuum of homeownership access and the benefits it confers: from disparities in credit scores and wealth, to mortgage access and loan pricing, to tax benefits, and, as has been increasingly apparent in recent months, to the valuation of homes in Black neighborhoods. While the focus in this brief is on Black households and communities, the structural racism that continues to shape Black disadvantage negatively affects Hispanic/Latinx and Asian communities as well, as evidenced by the disparate impact of both foreclosures and the COVID-19 pandemic for these groups.

COVID-19 and the social and economic upheavals that have triggered in the time of the pandemic work at these "norms" in two ways.

- They have been reframed in a sharper light of social justice, and in more than a few cases, are now regarded as intolerable ways to continue as local jurisdictions and societies.

- They are also being re-imagined as opportunity for profit-making private sector players to put into practice doing well by doing good.

A first action item for solutions seekers: Recognize the shortcomings of current data sets and benchmarks measuring equity and inequities in policy implementation.

Here Brookings Institute fellows, Randall Akee and Marcus Casey, articulate the challenge for detecting and dismantling some of systemic racism's impacts in housing and other aspects of economic equity.

The study of race and the consequences of race in market interactions have long been hampered by the relative lack of longitudinal data collected on relevant markers of discrimination, racism, and related long-term outcomes.

Former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld's famous quotation had it only partially right. There are knowns, unknowns, and unknown unknowns ... and there are knowns and unknowns people choose to never know.