Land

More Housing Needed In Cities Or Suburbs? The Answer Is Yes

It's not an either or. Migration and geographical population change statistics support residential investment and development in both dense, downtown urban hubs, as well as greenfield path-of-growth magnets.

The quote -- "there are three kinds of lies: Lies, damned lies, and statistics" – is often attributed to Mark Twain, who liked to use it. Twain himself credited its coining to a famed British statesman and former Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, whose papers don't mention the quotation.

Twain, Disraeli, or whomever, the turn of phrase has proved itself future proof.

It applies today in deriving meaning and business outlook implications from the statistical matrix of geographical mobility and housing attainability.

Here are a series of data points.

- From Pew Research:

There were an estimated 2.1 million more homeowners in the fourth quarter of 2020 than there were a year earlier, equal to the previous record increase in homeowners, which occurred during the housing boom between 2003 and 2004.

- From New Geography demographer Joel Kotkin in a New York Daily News column:

Despite all the talk of young people and families and others coming “back to the city,” suburbs accounted for about 90% of all U.S. metropolitan growth since 2010; over that time, suburbs and exurbs of the major metropolitan areas gained 2 million net domestic migrants, while the urban core counties lost 2.7 million.

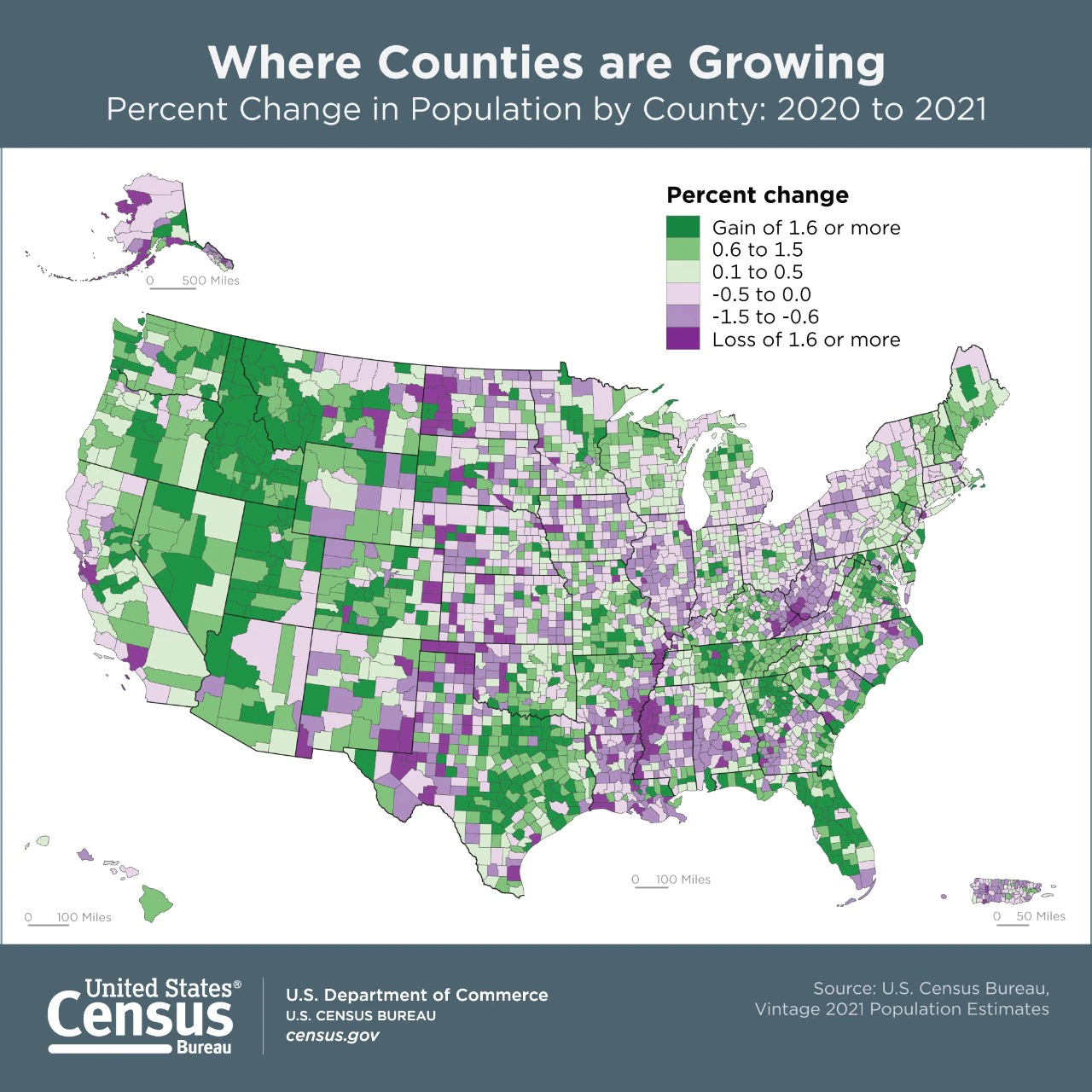

- From the U.S. Census Vintage 2021 estimates of population and components of change, released last week:

Five of the top 10 largest-gaining counties in 2021, were in Texas. Collin, Fort Bend, Williamson, Denton and Montgomery counties gained a combined 145,663 residents.

Los Angeles County, California experienced the largest population loss of any county, losing 159,621 residents in 2021.

Where the figures and the falsehoods surface is in often in the framing – or selective interpretation of the data in order to support a theory.

Joel Kotkin's macro New Geography view is that American big cities' time has come and gone. For Kotkin, suburbs are the the future. Census Bureau data would support only part of that assertion. While Los Angeles and New York City have seen negative population and migration patterns, other major metro counties, namely in Texas, are among the nation's leaders in in-migration and population growth.

What also fails to come to light in Kotkin's perspective are the many many suburban and rural areas that have seen declines. The Census' map of growth and decline shows, roughly, migration in and out of both suburban counties and urban centers. As the Census top line note observes, more than two-thirds of the nation's counties experienced a natural population decrease in 2021.

So, being a suburb, in and of itself, is no guarantee for growth and prosperity.

A truer common denominator to understand why places are either magnets or repellents for population in-migration is housing attainability.

As Pew Research notes:

A rising share of Americans say the availability of affordable housing is a major problem in their local community. In October 2021, about half of Americans (49%) said this was a major problem where they live, up 10 percentage points from early 2018. In the same 2021 survey, 70% of Americans said young adults today have a harder time buying a home than their parents’ generation did.

Los Angeles County alone counted 160,000 residents lost to out-migration during the July 2020 to July 2021 twelve month period, an exodus Mayor Eric Garcetti blames on soaring housing costs.

If you ask me the question, what are the top three issues facing Los Angeles or California, I’d say in this order: housing, housing and housing.”

Working age people will gravitate towards a place to live – urban, suburban, or rural – based on how they prioritize housing affordability, community attributes, and the time-and-expense commitment to their jobs.

Despite claims to the contrary, the jury's still out as to exactly how untethered people are – or not -- to urban core offices. So 2020 to 2022 migration and relocation trends may or may not reflect permanent or structural shifts.

The common denominator take-away, by and large, is that stark imbalances between rising demand and limited supply – not urban densification in and of itself – are the reason people are deterred from, repelled from, or drawn to a preferred place to live.

It's a misread to look at the data and declare that the era of the United States great cities as cultural, business, and residential centers has gone bye-bye. A Wall Street Journal story notes:

...Co-op and condo sales in Manhattan reached record levels last year, in part due to pent-up demand following limited activity in 2020. The median sales price for all apartments in the borough topped $1.1 million, the second-highest level of the past decade after 2017, according to the Douglas Elliman Rental Report prepared by Miller Samuel.

A more meaningful and more statistically valid observation – and one that business leaders in residential real estate and construction could put better use to – about natural population decrease in places like Los Angeles and New York is that, for people whose access to housing tends to be more need-based for financial reasons, and less discretionary, land use and zoning that contribute to scarcity also drive up prices, making it difficult to stay or to move in.

People with lower incomes or net worths were more likely to be renters: Only 10.5% of people in the top income quartile, for example, were renters.

Pew Research observes:

In 2020, 46% of American renters spent 30% or more of their income on housing, including 23% who spent at least 50% of their income this way, according to the most recent data available from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The statistics and their meaning, removed of what Mark Twain called their "beguiling" susceptibility to bending to his own pet theories suggest two equally valid conclusions:

- develop and build more for-sale and for-rent homes in the suburbs, and in the Sun Belt metros and counties that attract people who can make hybrid work circumstances with wider-open spaces and natural amenities within reach.

- develop and build more for-sale and for-rent higher density, vertical communities in urban downtowns, where people and households who might not have work-from-anywhere options or who prefer proximity to urban culture and convenience can access housing options as well.

It's not one or the other. It's both and. In both cases, more housing, period, is a solution – economically, socially, culturally.

Join the conversation

MORE IN Land

Rachel Bardis: Building A New Blueprint For Community Living

A family legacy in homebuilding gave Rachel Bardis a foundation. Now, as COO of Somers West, she’s applying risk strategy, development grit, and a deep sense of purpose to Braden—an ambitious new master-planned community near Sacramento.

Florida Paradox: In-Migration Vs. Growing Signs Of An Exodus

Even as domestic migration cools, international migration is driving demand, and with it, there is pressure on land prices, baseline costs, and housing attainability.

Housing’s High-Stakes Year: Six New Home Market Shifts To Watch

A massive liquidity crunch is reshaping homebuilding’s financial landscape. M&A is accelerating as builders chase capital and growth.