Leadership

Material Crisis Can Pivot Into Material Opportunity: Here's How

Choked off supply – like now, where at every turn, fatal-error bottlenecks, with temporary but indefinite timelines for restoration of normalized channel volume, clog visibility – can and will quell demand. Where's the opportunity?

Cue the armchair quarterbacks on what someone should have done differently to avoid the current fix everybody who's in the business of assembling 18,000 separate materials – not to mention their divisible subcomponents – into homes is in.

The pull is there. The push is shaky.

The reasons that's troubling, of course, is that it's anybody's guess as to how and when this so-called structural pull of demand may reveal its conditions.

Add up the variables. Current household incomes, near-term wage expectations, current interest rates, eventual increase expectations, near-term life-stage prompts like marriages, babies, schools, next-adventure lifestyles, etc.

Lots of flux, the one common denominator constant assumption being that there are a lot of people who need homes, from Zoomers to Boomers, with enormous cohorts of Millennials and GenXers laddering up in income.

The present, though is that in the sense that expanding supply can grow demand, the inverse can also occur.

Choked off supply – like now, where at every turn, fatal error bottlenecks, with temporary but indefinite timelines for restoration of normalized channel volume, clog visibility – can and will quell demand.

National Association of Home Builders vp for Survey and Housing Policy Research Paul Emrath tapped the trade group's May NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index survey responses. His mining of the data punctuates, in glaring detail, the level of risk current supply chain dislocation represents to work in process, to homes ordered but not started, and to backlogs worth billions of dollars pegged for delivery over the next 6 to 12 months.

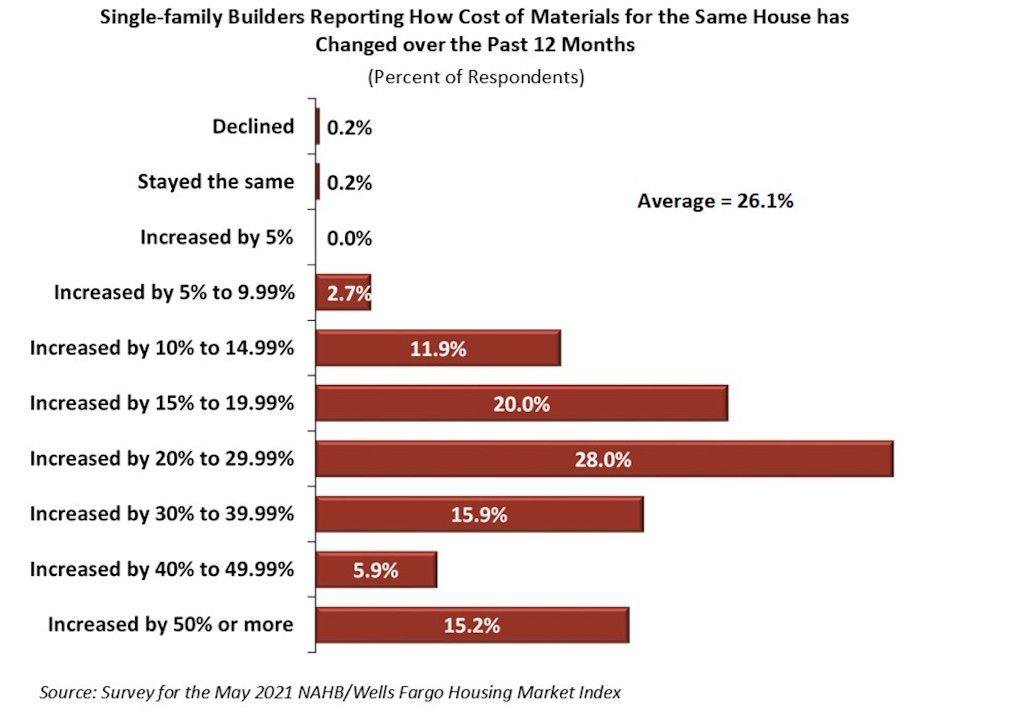

Emrath writes that among builder respondents to May survey questions about supply shortages and price increases, the most common response:

... (checked by 28.0 percent of builders) was that materials costs increased by 20 to 29.99 percent. However, 15.9 percent indicated that costs increased by 30 to 39.99 percent, 5.9 percent indicated 40 to 49.99 percent, and 15.2 percent even indicated that their costs had increased by 50 percent or more.

On average, the 12-month increase in material costs for the same house was 26.1 percent. Historically, NAHB has included the material cost question on its HMI questionnaire six times since 2012. The 2021 figure of 26.1 percent is the highest the average 12-month cost increase has been over that span—by a wide margin. The previous record was 6.1 percent recorded in 2017.

There's "coulda', woulda', shoulda'" accountability for this everywhere. What's striking about now is how everybody, in all of those newly re-kindled social gathering occasions we missed so much for the past year-plus, is talking not only about house prices but about lumber prices and the supply chain.

Everybody's now an expert on global trade disputes, the scarcity of microprocessors, the logjam of container ships, the Suez Canal debacle, the March 2021 Texas insta-freeze impact on petrochemicals, which lumber mills are at full capacity and when new ones are coming online, and how you now practically need to go to Ebay to find kitchen appliances.

Wall Street Journal staffers Gwynn Guilford and Sarah Chaney Cambon write this morning:

The shortages of goods, raw materials and labor that typically emerge toward the end of an expansion are cropping up much sooner. Many economists, along with the Federal Reserve, expect the jump in inflation to be temporary, but others worry it could persist even once reopening is complete.

“We’ve never had anything like it—a collapse and then a boom-like pickup,” said Allen Sinai, chief global economist and strategist at Decision Economics, Inc. “It is without historical parallel.”

Suddenly, it's kitchen table talk, this new-found and real-world appreciation for the work of sourcing, procurement, purchasing, supply chain, and logistics.

While land acquisition and real estate experts have long been the darlings of homebuilding enterprises – land speculation is a core business skillset for these companies – purchasing experts may finally get some well-justified credit for their value to these organizations.

Their view of their role is as stewards of both the homebuilding firm's interests and those of homebuying customers, whose excitement and engagement with a house starts with their direct experience of what purchasing strategists integrate.

The point here is this. Smart people in every industry set up operations around an alluring construct: just in time.

Just in time, lean, asset light, etc. These constructs prove out as engines to quarterly profit performance, and when institutional investment gatekeepers look under the hood of any organization they're evaluating for capital returns, just in time, lean, and asset light is what they want to see and they're going to reward it every time.

The allure is compelling. The logic is sound. The black-and-white executional implications are crystal clear. It's doable.

But, as New York Times staffers Peter S. Goodman and Niraj Chokshi report:

Over the last half-century, this approach has captivated global business in industries far beyond autos. From fashion to food processing to pharmaceuticals, companies have embraced Just In Time to stay nimble, allowing them to adapt to changing market demands, while cutting costs.

But the tumultuous events of the past year have challenged the merits of paring inventories, while reinvigorating concerns that some industries have gone too far, leaving them vulnerable to disruption. As the pandemic has hampered factory operations and sown chaos in global shipping, many economies around the world have been bedeviled by shortages of a vast range of goods — from electronics to lumber to clothing.

In a time of extraordinary upheaval in the global economy, Just In Time is running late.

There's nothing Wall Street abhors more than surprises. A model like just in time, nimble supply channel, can evoke comfort in many of our minds as a global business infrastructure that offers predictability.

Except when it doesn't.

For leaders in homebuilding and the hugely vested and invested interests that derive extraordinary value from relationships with homebuilders, the real lead of Goodman and Chokshi's fascinating dive into one of American cocktail parties' favorite topics du jour is buried in the last two paragraphs of the story.

Ultimately, business is likely to further its embrace of lean for the simple reason that it has yielded profits.

“The real question is, ‘Are we going to stop chasing low cost as the sole criteria for business judgment?’” said Mr. Shih, from Harvard Business School. “I’m skeptical of that. Consumers won’t pay for resilience when they are not in crisis.”

Like that one, here's the real lead of this story, which starts with focus on who should have done what to forestall housing's big mess and gigantic risk of the moment – which is to kill demand by failing to secure supply.

The lead is this: "Consumers won't pay for resilience when they are not in crisis," and, consumers do not live their lives in quarterly-earnings timeframes.

Consumers. Knowing them. Listening to them. Loving their emotional connection to where they call home and why that is. Gaining their trust and keeping it. Operationally, regarding purchasing as a truly strategic dimension of the community-making value chain, goes right along with staying close to consumers.

That's not a just in time, lean, asset light construct. That's a timeless value, and a very large opportunity for companies right now.