Policy

Epic Stretch For Housing Leaders: Local Land-Use Policy Wars

A land-use policy update: Pandemic, economic, and social upheaval foretell a more diverse and inclusive future of towns and cities.

Two appetites – one for safety and the other for growth – compete and conflict.

At scale, echoing Plato's assertion that The State is a "writ large" version of an Individual, America's towns, cities, counties and states mirror this instinctual tug-of-war with housing as their battleground. U.S. cities and towns – large, medium, and small – are a quiltwork of plays-within-a-play and the plotline in nearly every instance runs identically.

Roughly, the plot goes, resident-owners vie with resident-renters for access to, use of, and benefit from local value-creating or quality-of-life-generating resources. In most places, owner stakeholders carry more say in how these resources get used, and local elections serve simply as a way to perpetuate that weighting of influence disproportionately in favor of existing owners.

Net, net, as a consequence of these hard-wired stances and land-use policy practices in localities, two negative outcomes have reared up. One, economic, racial, social and cultural dynamism is at risk, and two, the market-rate new construction universe has shrunk, while more and more people are priced-out of that market and relegated to a negative feedback loop of financial, educational, and social stagnation.

- We see this as a housing-as-a-solutions opportunity.

- We also see this as a business leadership challenge.

These issues have been around the block for decades, but together, they make for an epic 2020s challenge. They're uncharted territory in both the way investment, planning, development, policy and construction can apply to society's growing passell of "improvement opportunities," and, in the way housing leadership skills need to evolve to thrive in a stakeholder-value-focused future of business.

Residential builders, developers, investors and their partners mostly have long viewed local land-use policy – restrictions, usurious fees, wasted time and bureaucratic inefficiencies – as a business externality they don't and won't ever control. So, it's an area of impact to business that gets little to no attention or effort. Of late, however, that "received knowledge" is getting a thorough going over in a business and policy environment where structural inequities are the target of wider and deeper scrutiny.

Let's frame this exploration, as we'll return to it again and again until we've been able to tap solutions-seekers to a number of new templates and models to defuse and decrypt self-perpetuating behavior that leads nowhere good and healthy.

Before 2020, a handful of U.S. cities and states awoke to new possibilities in efforts to expand the box of fair, decent, attainable housing access – inclusive, diverse, real-world.

Upzoning, a term coined to describe both queasy awareness of the absence and determination of allowance of more housing typologies – single-family, multifamily, multigenerational, multi-use structures of varied size and footprint – in any given jurisdictional zone, emerged as a societal tool. That tool, at essence, would balance, as well as it might, two forces most view as clashing: the preservation of a valued-familiarity and predictiveness versus the evolving, re-energizing replenishment of society's most important sub-ingredient, new, younger people.

Upzoning broke through in 2018 and 2019 as a nightmarish term for some, a threat tantamount to the "end-of-days" in the single-family detached market-rate housing part of the housing community. But as the National Association of Home Builders notes, diversifying housing types can be a boon to all comers.

Although this policy mandates the allowance of multifamily units on land previously only available for single family, it does not, in fact, outright prohibit single-family zoning or development — one can still build single-family houses in Oregon. In fact, the bill should give builders and developers more flexibility and opportunities to build an expanded range of housing types in the state.

The bill also requires that metropolitan service districts with populations of more than 10,000 and less than 25,000 allow duplexes on sites that were previously available only for single-family units.

Now, a quartet of crises – coronavirus, economic maelstrom, social upheaval, and seismic educational disruption – have together riven the bulwark of local government and community structural assumptions and inputs. At least momentarily, the four forces of nature have jammed open long-standing barriers to housing as a solution for futures that balance both the need for safety and the need to evolve and grow.

Here's a couple of recent insights, each of which sharpens focus on an intersection of matters – diversity, equity, dynamism, inclusion, justice, value-creation – on this issue that society and business haven't yet modeled elegant balances for.

In this piece, from Bloomberg's CityLab site, Salim Furth, a senior research fellow and director of the Urbanity Project with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in Virginia, sets the context for discovery of a solutions-focused approach to the chronic pain-point. He writes:

A constituency seeking more diverse, affordable housing in economically vibrant places keeps gaining traction. Most recently, several California cities have joined places like Minneapolis, Seattle and Oregon in chipping away at the single-family zoning regulations that have enshrined suburban-style detached homes as the dominant form of housing in America’s metros.

Foes of such “upzoning” efforts often frame these reforms as existential threats to suburban life. Understanding President Joe Biden’s position on the matter will mean looking beyond this kind of rhetoric. How will his administration react as a growing number of states and cities tackle the affordability problem head-on? Is he willing to join local leaders in rethinking some of his suburban supporters’ sacred cows?

The Builder's Daily's own Dream Team member Jeff Handlin, president of Denver-based Oread Capital and Development, writes of Professor Furth's piece:

What a thought-provoking article. It is so important we dismantle exclusionary zoning and in its place, create policies that encourage the market to provide a full-spectrum of housing. Diverse housing choices make more diverse neighborhoods, and the converse is also true.

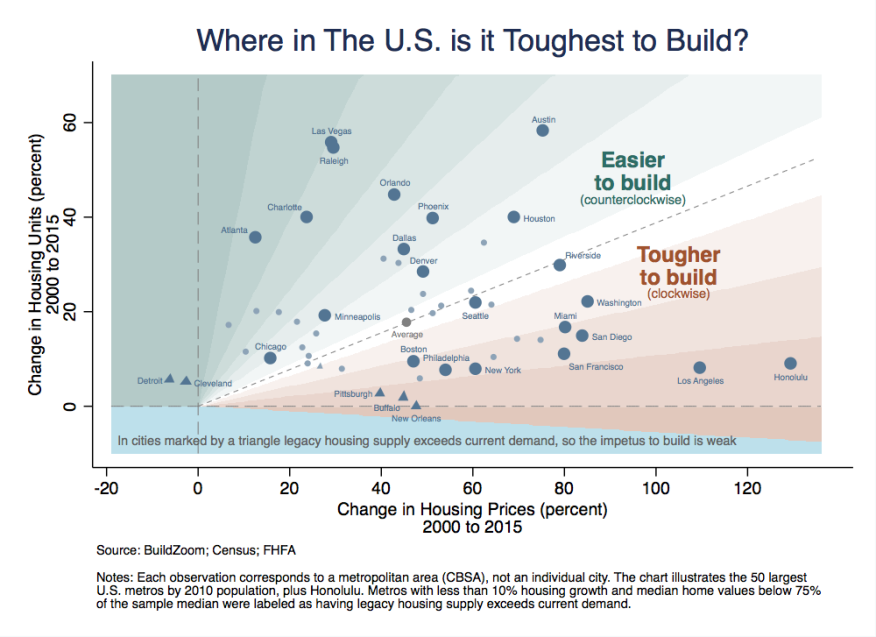

Here's access to a deep-dive policy analysis Furth did with two of his colleagues at George Mason, a piece that clarifies the "false choice" between safety and dynamism. As well, one of those colleagues, author and George Mason visiting fellow Kevin Erdmann, penned this Wall Street Journal [pay-gated] piece, "Rich Cities Created the Housing Shortage," which, again shone a spotlight on a vicious-circle of protectionist local policies that in the end will amount to a lose-lose.

For decades leading up to the [2000's housing meltdown] crisis, closed-access cities accumulated rules restricting new construction. This produced trillions of dollars of wealth for existing urban owners and prevented millions of Americans from moving to where they could be teachers, nurses and custodians for the companies and employees who design software, medical devices and autonomous cars.

Here, the ULI Terwilliger Center’s 2021 Home Attainability Index spells out – in human tolls – downstream, real-time impacts of unchanging local land-use constriction.

The most severe cost burdens among middle-income households are predominantly found in the most populous regions. However, there is a nationwide lack of attainable homes for critical members of the workforce that is not limited to the United States’ most vibrant metropolitan economies; In particular, there is a national struggle for lower-income households to find attainable rental units; and Segregation – both by income and race – cuts across market types and geographies, and high housing costs threaten to worsen racial and socioeconomic disparities.

These conditions will not disappear as a result of continuing to behave as we have in the past nor the passage of time. They describe a crisis, one that will worsen unless people and things change, in which case it can get better.

A consequential question challenges housing's market-rate single and multifamily enterprise leaders now. It is this. How ripe are municipal, county and state elected and appointed officials and their voter constituencies for self-disruption? The predicament is further amplified amid "fad-or-trend" debates, assertions, spins, predictions, and promotions.

Recently, we talked about this challenge for a Forbes piece with Carol Galante, former deputy secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development under President Barack Obama, and now I. Donald Terner Professor in Affordable Housing and Urban Planning and founder-faculty director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California at Berkeley.

“In both the private sector and among earnest and enlightened people working in the public sector, we’re seeing active efforts to stretch out of the past into the future," say Galante. "We’re not going to get to the solutions we need unless we marry policy change with innovations in practice and innovations in the way we finance projects and community development, and in how we define ownership and stakeholder-ship. We’re seeing great strides of progress everywhere in how we build housing, how we get it approved, and how we get it financed, and we have to work to apply these innovative techniques to create results where housing can be a solution for where the crises hit the hardest.”

Galante, like others, believes that, as much as the four-pronged crises have triggered sweeping measures of devastation and damage, they may, by the same token, have forcibly removed friction from some of the grinding gears of positive change.

“It’s always a challenge for policy—particularly local land-use policy—to keep pace with building technologies advances, and, lately financial ones,” Galante notes. “If anything good can come out of the enormous distress the pandemic has created it’s what I’d call an emerging coalition of the willing on the policy front that have both been exposed more profoundly to wealth and income disparities among people of color and society’s most vulnerable populations, and experienced, first-hand, a sense of possibility around what’s achievable.”

Step-change in housing and development enterprise leadership chops may mean that a leader can and must lean into stakeholder value creation, not just in the business sense, but in how public-private partnerships spark and take hold.

To continue to view regulatory burden strictly as an uncontrollable externality is a choice, not an inevitability. Successful leaders will learn to shelve the "givens" that put preservation of norms necessarily at odds with dynamism and growth.

Remember:

- NIMBY–Not In My Back Yard

- YIMBY–Yes In My Back Yard

- NIMEY--Not In My Election Year

- NIMTOO--Not In My Term of Office

- LULU--Locally Undesirable Land Use

- NOPE--Not On Planet Earth

- CAVE--Citizens Against Virtually Everything

- BANANA--Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything

The common denominator here – us vs. them – is now either us vs. us, or more simply, us.