Marketing & Sales

Moving-Target Relocations: Truck-Loads Of Mobility Data

Atlas Van Lines, U-Haul, and United Van Lines' perennial truck-race for earned media attention on America's migration took on pandemic proportions as COVID-19 impacts spread into 2021.

Good, good, good, good migration.

Anywhere you turn for data evidence, the future looks oh so bright for migration's continued sweep toward America's Sunbelt "smile" states.

Each year, three American stalwarts in the field of moving and mobility – Atlas, U-Haul, and United Van Lines – vie for headlines, soundbites, and social shares by mining the data of originations and destinations in their own customer logs, and calling them a migration study.

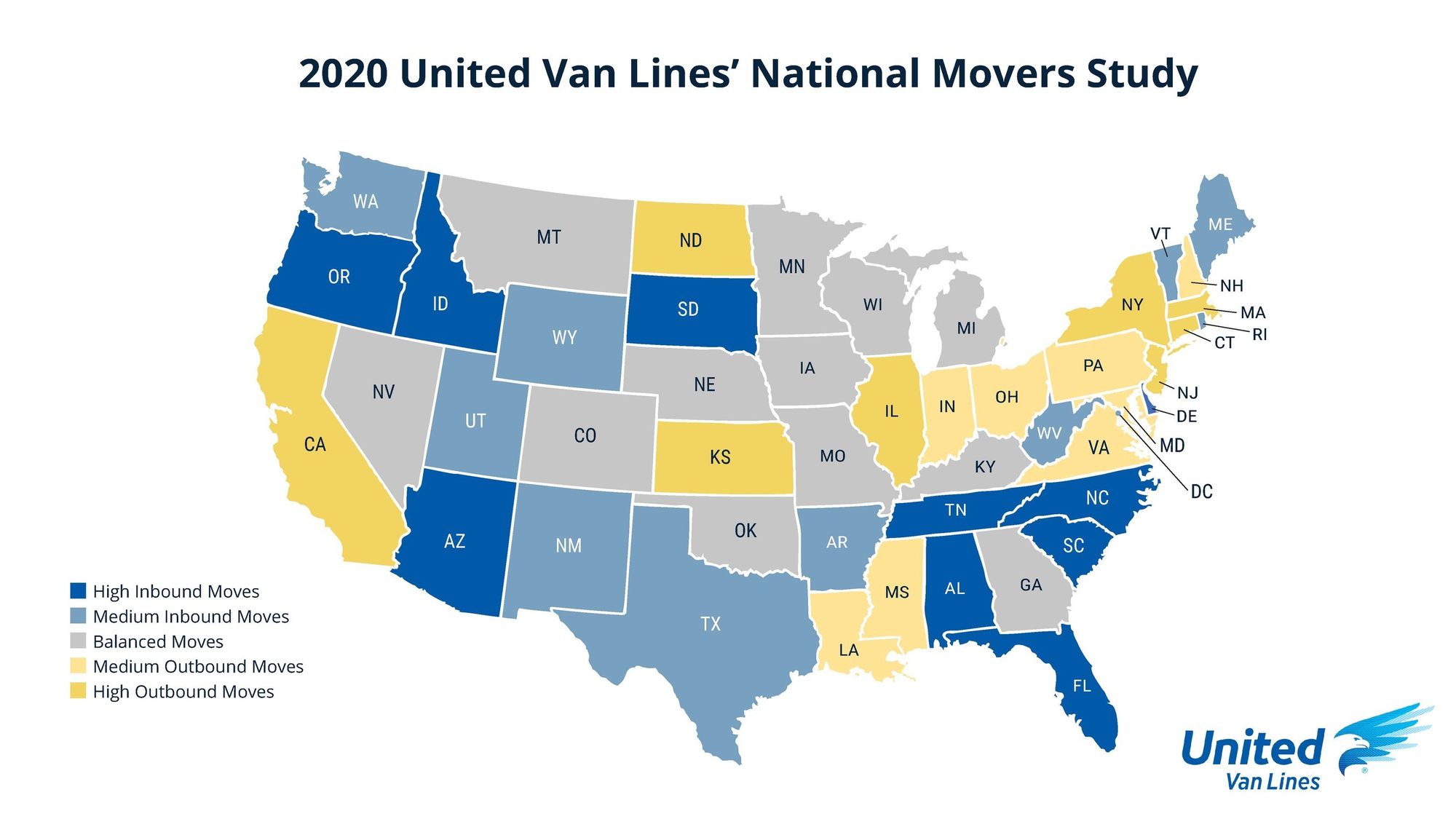

For instance, Atlas bases its sexy inbound, outbound, and balanced color-coded U.S. map on its log of 64,858 interstate and cross-border household goods relocations from January 1, 2020 through December 11, 2020. United Van Lines' calculations derive from destination states that clock in with more than 250 of its movers, and U-Haul says its data is compiled from more than 2 million one-way customer bookings for its vehicle fleet.

In 2020, Tennessee claimed the top spot for the most one-way U-Haul arrivals versus departures for the first time ever. Arrivals accounted for 50.6% of all one-way U-Haul traffic in Tennessee, according to U-Haul, a 12% increase over last year. Meanwhile, departures rose only 9% over 2019. Florida, which came in first in 2019, came third. Texas, which has ranked in the top two states with the most one-way arrivals since 2015, was No. 2 in 2020. Florida, which came in first in 2019, fell to third.

So, it's head-scratching that the United line-up for inbound movers ranks Tennessee as only No. 7, and the state doesn't even crack the top 10 in the Atlas ranking of destination states.

Here's a piece from Wall Street Journal staffer Candace Taylor, whose reporting zeroes in on the ins and outs of mobility and migration in Florida, a state known to be one of the most active new residential development and construction markets.

Each year nearly as many people move out of Florida as move in. They are fleeing hurricanes, heat and escalating home prices. While Covid-19 has prompted some out-of-staters to buy homes in Florida, the state’s population growth has slowed in the pandemic to its lowest rate since 2014, according to the state’s November 2020 Demographic Estimating Conference. Between April 2019 and April 2020, the state’s population increased by 1.83%, or 387,479 people. Between April 2020 and April 2021, however, the population is expected to grow by 1.38%, or 297,851 people.

Framing biases, false equivalencies, varying data inputs, and apples to oranges comparisons among the three sources give each one of them a "worth-a-look" measure of validity.

A perspective to remember here. The incidence, and growth and decline trends that measure in-year activity for mobility trends fall within a broader context of a drawn-out multi-decade slow-down in mobility and migration patterns, particularly when it means moving from one state to another.

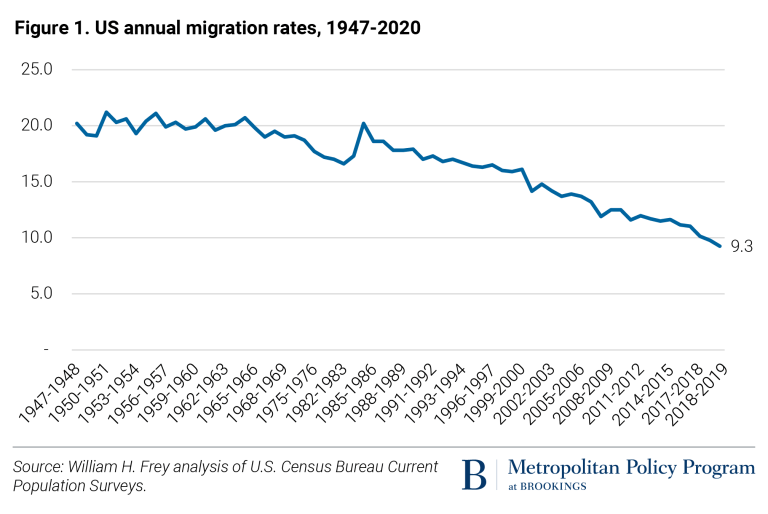

Freddie Mac research "shows that U.S. domestic migration rate has declined steadily over the last 50 years, hitting an all-time low (9.8%) between 2018–19."

Ultimately, the most reliable resource for rigor in the area of domestic migration is Brookings Institution senior fellow and University of Michigan research professor William Henry Frey.

Likely as not, Dr. Frey will take a breath before jumping to conclusions as to the magnitude or longevity of pandemic impacts on migration and mobility. A demographer by training and by nature, he's not prone to impulse.

Note, for example:

There now appears to be a new mix of migration patterns across different parts of the country, as evidenced by real estate, moving, and survey data suggesting selective migration upticks and downticks due to both safety and economic concerns.

Still, newly released pre-pandemic census statistics show a continuation of the decades-long migration decline, bringing the percentage of Americans who changed residence to a post-World War II low of 9.3%. This one-year rate—between March 2019 and March 2020—occurred on the heels of a year when the nation’s total population growth fell to a 100-year low, with a continued downturn in the nation’s foreign-born population gains. Thus, even before the pandemic, the nation was in the throes of stagnating demographic dynamics.

What matters most for residential real estate and construction stakeholders, in other words, may have to do with a broad, deep, and long-range trend of stagnation. Twitchy, flight-to-safety reflexes–as pronounced as they appear to be--could be false indicators of what's to come, which will more likely revert to that longer-range tendency among American householders to stay put.