Policy

Housing's Importance As US Stares Covid-Delta In The Face

Battles with local, regional, state, and federal regulators currently pass too much cost burden to people sitting at kitchen tables. What can and should housing's leaders do about that now?

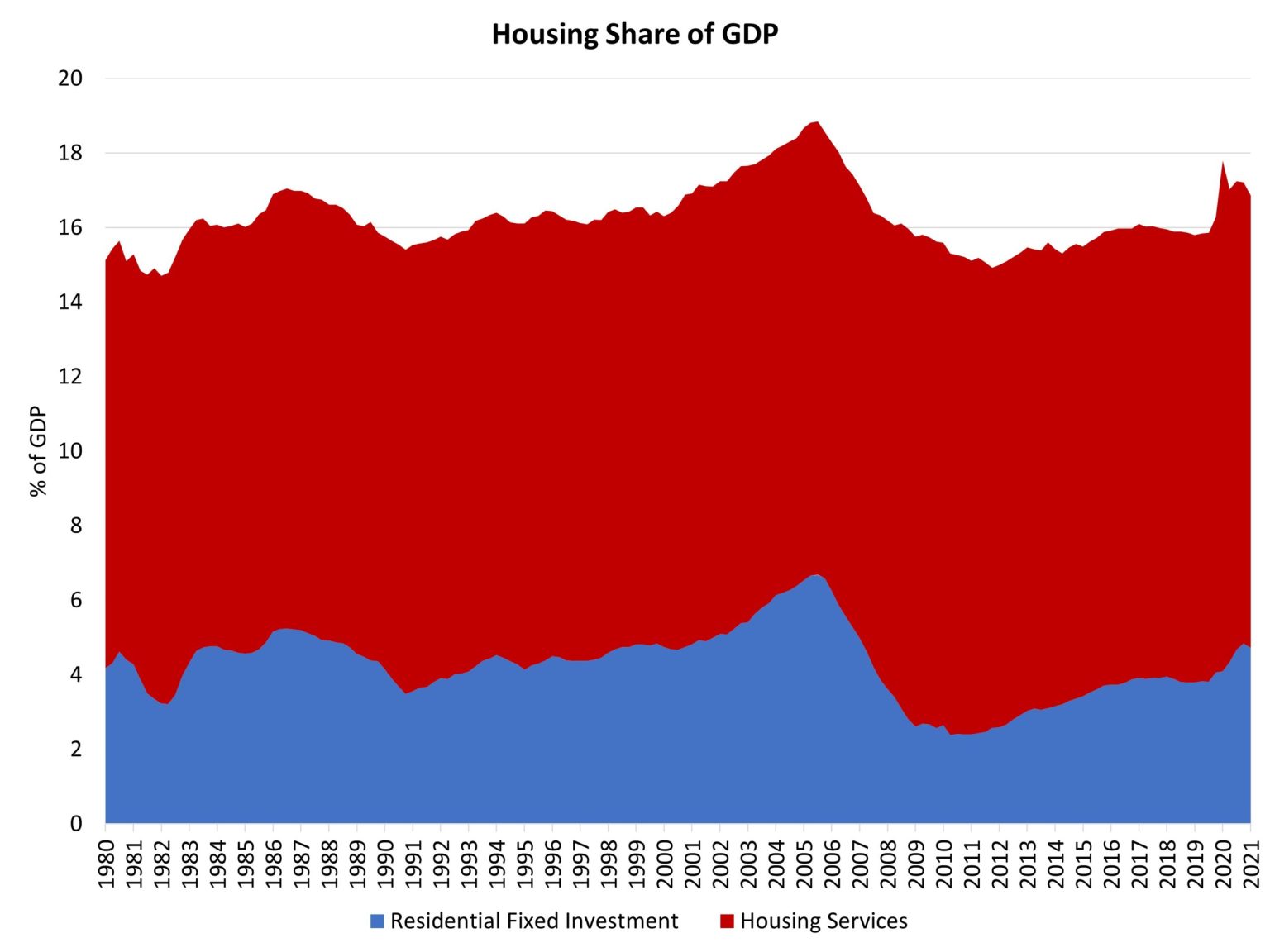

- A smidge less than one of every five GDP dollars in the American economy

- Just shy of $4 trillion

- Just off a 14-year high-water mark

These are characteristics, in broad strokes, of housing's clout. By the way, although they're mind-blowing measures in and of themselves, they don't begin to quantify their multiplier-effect influence on consumer spending, on job creation and ongoing payroll headcounts, and entrepreneurial activity, and economic activity in the manufacturing, distribution, municipal agency and other governmental activity.

As a value generator in the U.S. economy, no single industry sector can match it.

National Association of Home Builders chief economist Robert Dietz writes here, Housing is nearly 17% of GDP.

Housing-related activities contribute to GDP in two basic ways.

The first is through residential fixed investment (RFI). RFI is effectively the measure of the home building, multifamily development, and remodeling contributions to GDP. It includes construction of new single-family and multifamily structures, residential remodeling, production of manufactured homes and brokers’ fees.

For the second quarter, RFI was 4.7% of the economy, recording a $1.07 trillion seasonally adjusted annual pace.

The second impact of housing on GDP is the measure of housing services, which includes gross rents (including utilities) paid by renters, and owners’ imputed rent (an estimate of how much it would cost to rent owner-occupied units) and utility payments. The inclusion of owners’ imputed rent is necessary from a national income accounting approach, because without this measure, increases in homeownership would result in declines for GDP.

For the second quarter, housing services represented 12.1% of the economy or $2.8 trillion on seasonally adjusted annual basis.

Taken together, housing’s share of GDP was 16.9% for the quarter.

Now, maybe not at the average kitchen table, but in many other respects, people in society look at builders, developers, remodelers, residential investors, etc. as part of housing, as pieces of a whole. Together, you're a singular, big complex of players who exert a lot of sway on lives, on communities, on economics, and on our culture.

For many, and for a good number of people in locally-elected municipal, county, and regional governments, housing is, in their minds, an industry.

Everyone working at the jobs of building, of development, of architecture and planning, of manufacturing, of lending and capital investment – from the jobsites to the double-wides to the divisional offices to the corporate headquarters – knows that this is not really how their work, and impacts, and influence rolls up.

However, for consumers, taxpayers, voters, members of society, etc. companies that participate in residential investment, development, and construction are imagined as a collective, coherent whole.

If more builders, developers, and real estate investors recognize, understand, and fully appreciate how society perceives them – as an industry that represents and tallies up to nearly a fifth of the U.S. economy – more realistic, trusting, and productive relationships could result in housing's function as a societal solution for challenges places – tiny, middling, and large urban areas and sprawling rural areas – need to address.

Like health and safety, and education and training, and protecting the climate from further damage, and economic justice, equity, and mobility. And American dynamism.

Housing is the economy's leading producer of value. It's Door Number One. Its leaders must understand that that standing in our economy comes with strings attached.