Technology

Homebuilding's Endangered Species: Margins Of Error

A last bastion refuge of new residential construction business practice has reached the brink of elimination as inflation, interest rates, supply chokeholds, and local-municipal delays narrow the fairway.

They've been around for so long in homebuilding and its fiercely complex and ingrained community of practice, they're taken for granted.

Through thick and thin, they've been there – hiding in plain sight – to draw on as necessary when the time called for them, as it always did.

They are homebuilding operators' margins-of-error. The field has always lived with them, depended on them, and expected them to be there when needed. But now, they're rapidly entering into classification as rare and endangered species as pandemic-era policy, economics, geopolitical, and social macro tides converge into a moment of inflection.

Enter the Four Horsemen of the latest housing boom –

- input cost inflation

- runaway mortgage interest rates

- unending supply chain chokeholds,

- and various and sundry obstacles on the local entitlement, permitting, approvals, inspections front.

Margins of error – for what they are and the role they've always served as a handy way to navigate construction operations' intricate, often hodgepodge-ish coalescence of hyper-local, regional, national, and global resources – run the risk of extinction as the Four Horsemen raise hell and take no prisoners.

Builders, it's understandable, hate to admit they could go away. Seemingly forever, they're all that stood to buffer them from a sober recognition that, building the way they do, visibility and predictability – requirements for practically any manufacturing operational and business model – would remain in a fantasyland. Here's how Construction Physics' Brian Potter lays out that reality.

Buildings are complex artifacts: a typical single family home has somewhere in the neighborhood of 3,000 parts, and an apartment building might have 10 to 100 times as many depending on the size. For comparison, a typical car has somewhere around 30,000 parts, and a Boeing 737 has around 600,000.

These parts are put together in a specific way, in a specific order, by dozens of different workers. Assembly tasks are highly interdependent, and each step of the process depends on the previous steps being completed successfully - install the insulation wrong, and you’ll delay the installation of the drywall, which pushes back trim, which pushes back painting, etc. Construction in some ways faces a uniquely difficult assembly task - the site-built nature of the product means it’s hard to parallelize component production (I can’t get a jump on the electrical by starting it before the framing is done), and the trade-specific nature of the tasks means there’s little labor flexibility (if your framer doesn’t show up, you can’t take half the HVAC crew to start cutting studs so the project stays on schedule).

Building production is also characterized by a great deal of uncertainty and factors outside the builder’s control. The physical environment is often difficult to predict (whoops, we got seven days of rain, whoops, we found a huge boulder when we were excavating), as is the cultural and regulatory environment (whoops, the zoning board is making us remove 20 units, whoops, the plan reviewer is saying we need to add more brick). On top of this, the building design process results in much less information compared to other types of production - the drawings used to put up the building don’t come with a step-by-step set of instructions, or a complete list of parts.

Each of a typical new home's 700 SKU and its Russian Dolls-nest of subcomponents, each process and its interrelated series and sequences of subprocesses, each end-to-end value build cycle and its tens of thousands of matters of precision, price, and downstream impacts, etc. is its own discrete P&L statement with margins of error in and throughout. Margins of error, then, allowed builders to linger on in a massive system of puts and takes, where dysfunction and function perpetuate and co-exist, and where money could make up for lost time, and hurrying faster could nearly always narrow the losses of extra financial expense.

With margin-of-error cushions at virtually every intersect and hand-off, the paper trail of operational excellence and financial accountability could go on under the hood as long as an end result stood for itself as success, or a relatively believable promise of it. Ways to hide or at least play down the tracks of inefficiency, of mismanagement, of overspending, or waste of some other sort often traced back to those margins of error.

Now, the Four Horsemen are carrying on a ruthless campaign to search and eliminate each and every remaining one of this slush funds of operational wiggle room.

The margin of error is significantly lower than it has ever been," says Salman Ahmad, ceo and co-founder of Mosaic. "As costs increase so fast, and supply chains come apart, and labor gets stretched thinner and thinner, and construction cycles elongate longer, the only recourse is to seize on opportunities for visibility and predictability, because managements are beginning to realize those days that they could live and even thrive within those margins of error are never going to come back again."

Mosaic today has released a second round of survey insight into homebuilding industry-wide adoption and interest in a range of building and management technology and data solutions, with evidence homebuilders are pushing into a "technological tipping point as they look for new ways to work smarter and more efficiently to maintain current production levels."

In Ahmad's view, the long elusive business and operational bulwarks of predictability and visibility are accessible, i.e. they're no longer a pipedream but an essential dimension sustainable profitability in a more resource-constrained future of homebuilding. Rather than hold out and continue to rely for viability and success in the domain of margins of error, Ahmad notes, more builders are committing, investing, implementing, training, and integrating technology and data solutions. What Ahmad finds fascinating is an accelerated embrace among homebuilding operators and strategists, even as The Four Horsemen wreak havoc in what was to be – and many still expect will be – a bang-up, ladder-wrung upward year for homebuilding in 2022.

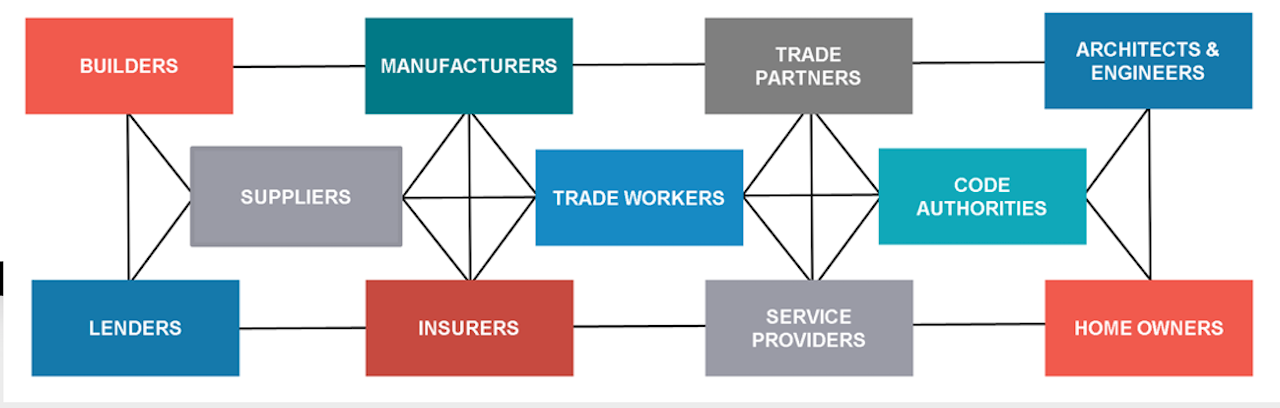

The adoption and progressive use of technology we're seeing builders evolving towards as they try to get back in step with homebuyer and single-family rental demand falls into three buckets," Ahmad notes. "Number 1 is reporting, where clean, holistic, real-time, increasingly automatic data can take the place of anecdotal data, which is often lagging and isolated. A second dimension is in management tools that can shore up accountability in ways that impact the whole process, inclusive of positive effects with the building trades, because these days, trade networks and trade relationships turn out to be far more important than even capital relationships to get work done. The third area of technological investment and impact, of course, is in product, the construction, factory-based, pre-fab, and integrated assembly capabilities."

The recently harvested Mosaic insight on technology investment and adoption – when peeled back to its raw data break-outs – reveals a stronger lean-in to technology, logically, where volume and demand for housing activity is highest.

Ahmad notes that particularly where a double-stream of household demand – for both single-family for sale, and single-family built-to-rent homes – is smacking up against capability constraint, the disposition among builders to invest in and operationalize technology solutions has accelerated.

Single-family built to rent has three sources of rocket-fuel unlike other assets in the residential real estate continuum," says Ahmad. "Consumers definitely want it, either for financial reasons or by choice; investors love it because of its profile investors can own as a cash-flowing, net-present value holding; and builders like it because of a trade base that's already established and integrated. The gap, now, between potential development and actual building capability can only be closed with technology solutions, because there's little to no margin for error to fall back on, and there's such a huge upside if builders can leverage visibility and predictability to get good at it."

Join the conversation

Residential construction made easy. As a tech-enabled general contractor for the residential development industry, Mosaic focuses on production-scale projects of all types, from single-family homes to horizontal apartments to other build-to-rent product types.

MORE IN Technology

AI Isn’t Optional: Marc Minor’s Call To Homebuilding Leaders

At The Builder’s Daily Focus on Excellence Summit, Higharc CEO Marc Minor urged homebuilding executives to do two hard things at once: run lean—and build the muscles for continuous innovation through AI.

HistoryMaker Homes Reinvents Itself From The Data Up

Chief Digital Officer Ty Brewer’s digital transformation playbook aims to drive operational unity, accountability, and agility in a turbulent market environment. The Builder's Daily unpacks the process.

Andrin Homes Turns Customer Pain Into Business Culture Shift

Facing the toughest Toronto market in decades, Andrin operationalized a proactive homeowner experience strategy. What started as a service platform became a catalyst for team alignment, trust, and performance.