Land

Florida Paradox: In-Migration Vs. Growing Signs Of An Exodus

Even as domestic migration cools, international migration is driving demand, and with it, there is pressure on land prices, baseline costs, and housing attainability.

Florida’s population growth exploded during the pandemic, driven by international and domestic migration, and pretty much kept up that torrid pace through last year.

Nationally, immigration drove most of the U.S. population growth in 2024, a pattern that began in 2020. It became a sore point for those trying to curtail immigration, and President Trump made the issue a cornerstone of his platform in his campaign last year.

Since taking office in January, Trump has clamped down on immigration and accelerated deportations, heightening concerns about their impacts on the skilled workforce for building new housing and the downstream effects on the U.S. economy.

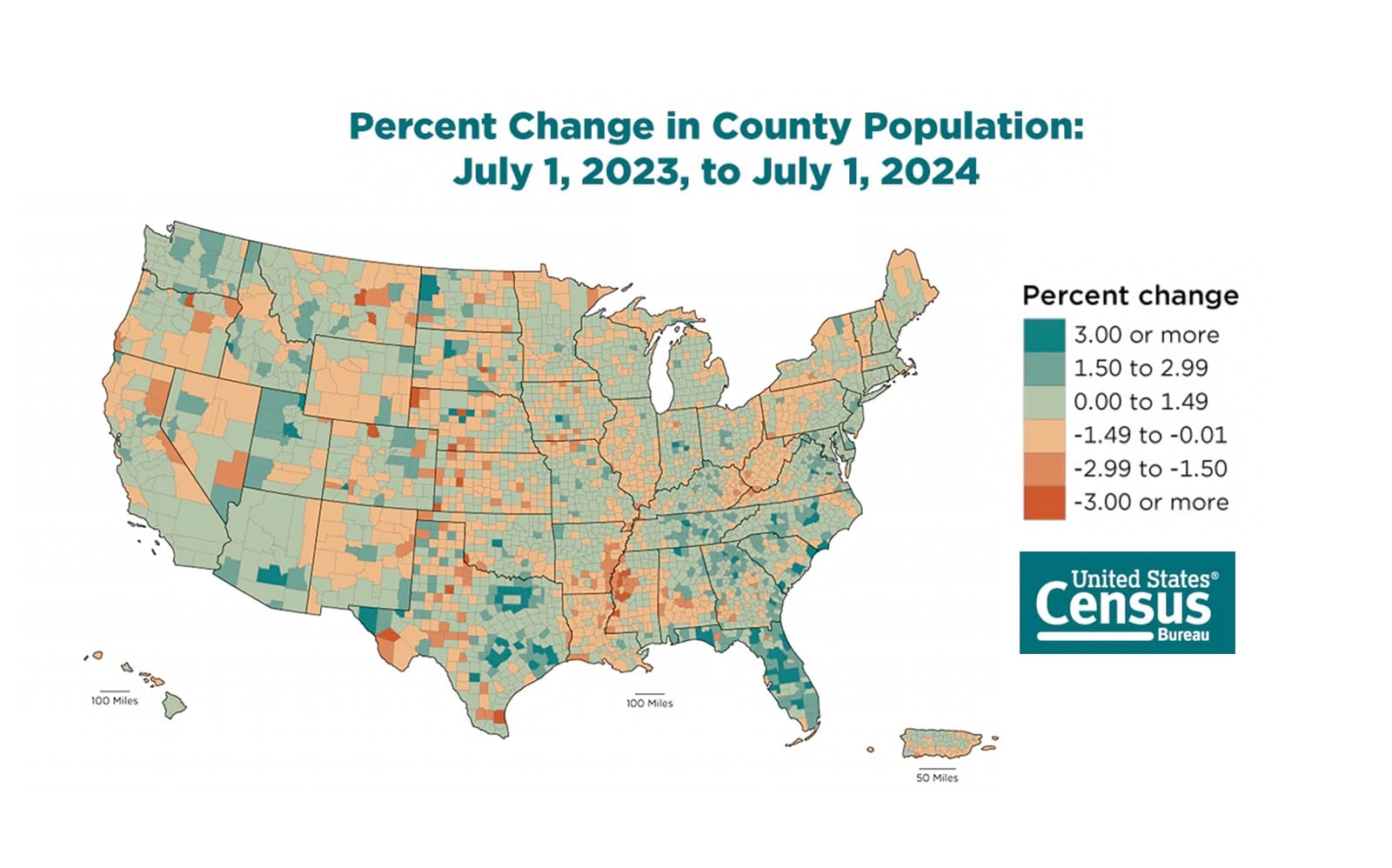

According to recently-released Census data, the Sunshine State's population gain between July 2023 and July 2024 was second only to Texas' 562,941, with a 467,347 gain.

[Source: U.S. Census Bureau]

[Source: U.S. Census Bureau]

Central Florida metropolitan areas Orlando and Tampa emerged as the biggest winners in net domestic migration across the state in new Census data released late last week.

South Florida’s Miami metropolitan area, which grabbed headlines because of major financial firms moving there, has lost momentum on domestic net migration over several years and, instead, has grown primarily through immigration.

Census data shows that the Orlando and Tampa metros benefited from both forms of migration.

Housing prices skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic in each of the metros.

Central Florida's in-migration mojo showed up clearly in last year’s residential construction and land sales. According to Georgia research firm MarketNsight, the Orlando and Tampa metros were in the top 10 for single-family building permits nationwide, with 15,434 permits and 13,454 permits, respectively.

Land sales prices for residential development followed suit. While total land sales across Florida slowed last year, Central Florida was active, and prices rose substantially, according to a report from Saunders Real Estate, a Lakeland, Florida brokerage.

The firm tracks sales along the Interstate 4 corridor, which includes 18 counties between Florida’s east and west coasts. Thus, the report captures sales. Saunders’ report shows that land and lot prices increased in most of the counties.

- Price Increases:

- Residential land prices in the 12 counties averaged $97,136 per upland acre in 2024, up from $73,690 in 2023.

- Platted lot prices increased in 17 counties, averaging $92,977 per lot in 2024, a 23% increase from $75,551 in 2023.

- Top Central Florida Counties:

- Land prices per acre: Seminole, Orange, Pasco, Sarasota, and Brevard.

- Number of acres sold: Polk, Pasco, Lake, Manatee, and Sarasota.

- Lot prices: Martin, Indian River, Orange, Sarasota, and Seminole.

- Number of lots sold: Polk, Pasco, Manatee, Osceola, and Sarasota.

Saunders notes that builders generally prefer finished lot prices to be around 20% of the final home sale price. Rising lot prices would mean new – higher – home prices would follow.

Central Florida experienced rapid housing price increases during the pandemic due to the influx of new people, which, like many places in the South, caused affordability concerns. Median home prices across the Central Florida region increased last year.

Immigration Impact

A debate erupted last year over immigration's role in making housing less affordable. During his vice president debate last October, then-V.P. candidate J.D. Vance said:

You have got housing that is totally unaffordable because we brought in millions of illegal immigrants to compete with Americans for scarce homes.”

Vance echoed what President Trump had been saying on the campaign trail. Those wanting to curtail immigration agreed.

Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies disagrees. Riordan Frost, a senior research analyst, writes that rents and home prices rose quickly before the immigration surge that began in 2019.

One major factor in demand was the historically large millennial generation (born 1980–1994) being at prime homebuying ages (aged 26–40 in 2020) with years of pent-up demand from delayed household formation after the economically damaging effects of the Great Recession,” Frost wrote.

Most economists and housing business strategists we speak with assert – publicly and privately – that immigrants do not comprise any negative effects on demand or attainable access to housing among households seeking homes. What immigrants materially do represent are an important part of the solution to America's pervasive housing supply constraints.

While population growth is important, real estate developers also consider household growth. Still, migration leads to household formation, which logically leads to a need for more housing.

According to Census data, net international migration represented nearly 7.2 million of the 8.6 million population gain between 2020 and 2024. Natural change – natality vs. mortality – the difference between births and deaths, accounted for 1.4 million.

The pandemic accelerated internal movement to the Sun Belt, particularly Florida and Texas.

Orlando’s largest domestic migration occurred from 2021 to 2022, with 37,000 people, dwarfing the previous year’s 6,900. It slowed to roughly half that in 2022 to 2023 and then to 779 last year. Over the 2020 to 2024 span, international migration brought 172,000 people, more than 100,000 more than domestic migration.

In Tampa, domestic in-migration of 161,000 was nearly 50,000 higher than international migration over the multi-year period.

Miami scored a major win in 2022 when the $66 billion hedge fund Citadel Capital announced it was moving from New York to Miami. Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, and Morgan Stanley, along with other notable financial firms, set up shop in West Palm Beach. In response, apartment and condominium towers began rising.

However, while the Miami metro area was winning companies, people were leaving, a trend that even predated the pandemic. Analytics firm ResiClub showed that Miami has trended in the red on net domestic migration since 2018.

Between July 2023 and July 2024, Miami experienced a net negative domestic migration of more than 101,000. That puts Miami in the same out-migration league as New York City, which lost nearly 177,000, and Los Angeles, which lost 122,349.

Still, the Miami metro’s total population grew over the period, making it the country's sixth-largest Metro. Census data showed that international migration played a big role in boosting total population growth. From April 1, 2020, to July 1, 2024, net international migration exceeded 553,000, while domestic migration topped 259,000. Miami was second to the New York City metro’s 721,673 over that period.

Over that period, New York City experienced negative net domestic migration of more than 1 million people, resulting in a net population loss of 368,488 people. However, last year, it also gained in population, but only because of international migration.

Dallas led the country in net domestic migration from 2020 to 2024, with 253,879 people, but net international migration was nearly 9,300 people.

Interestingly, Dallas had the second-highest natural change, at 188,913 in those years, meaning there were more births than deaths. Growing families also help drive housing demand.

New York City led the country in natural change with 236,519. However, buyers must venture far out into the suburbs to buy more affordably than in the urban center. For example, Putnam County, about 60 miles north of New York City has a commuter train line to Grand Central Station.

What This Means for Builders, Developers, and Investors

The headline here isn’t just that Florida — and Central Florida in particular — is still growing. It’s how it's growing, why, and what that means for housing’s supply-side decision-makers. Even as domestic migration cools, international migration is driving demand, and with it, there is pressure on land prices, low costs, and housing attainability.

The math is simple: More people equals more households, and more households mean more demand for housing. But meeting that demand in today’s environment— where skilled labor is harder to find, development timelines are slower, and the political climate around immigration adds risk to the workforce pipeline that makes housing possible — is not simple.

The growth stories in Orlando, Tampa, and even still in Miami tell us two things:

- Migration and household formation will continue to concentrate in a handful of regions, especially in the Sun Belt, regardless of short-term volatility.

- Builders and developers who succeed will be the ones who plan for population pressure and labor constraints at the same time—investing in people, partnerships, and process innovation that allow them to deliver at scale, even when the rules of the game shift.

Whether it’s finished lot pricing, immigration policy, or shifting demand patterns, the takeaway is clear: Strategy needs to live closer to the ground, where land, labor, and livelihoods intersect. That’s where resilience and opportunity still live, too. As D.R. Horton founder, the late Don Horton, used to repeat to generations of his team members a commonly-held cardinal principle:

All real estate is local."

MORE IN Land

Steel, Skeptics, And The Real Innovators In U.S. Homebuilding

TBD MasterClass contributor Scott Finfer shares a brutally honest tale of land, failed dreams, and a new bet on steel-frame homes in Texas. It's not just bold — it might actually work.

Home At The Office: Conversion Mojo Rises In Secondary Metros

Big cities dominate an emerging real estate trend: converting office buildings into much-needed residential space. Grand Rapids, MI, offers an economical and urban planning model that smaller cities can adopt.

Rachel Bardis: Building A New Blueprint For Community Living

A family legacy in homebuilding gave Rachel Bardis a foundation. Now, as COO of Somers West, she’s applying risk strategy, development grit, and a deep sense of purpose to Braden—an ambitious new master-planned community near Sacramento.