Fall Focus: 3 Lenses A Housing Leader Needs For '22 Results

A French novelist Gustave Flaubert said

My foregrounds are imaginary, my backgrounds real.

American homebuilders and their business and construction partners – facing tens of thousands of work-in-process that need insulation, electric, HVAC, and plumbing, drywall, exterior cladding, interior trims and doors, kitchen and vanity countertops, cabinets and appliances, carpeting, tile, other flooring, lighting, and plumbing fixtures to deliver, many of them in the next 60 to 70 days – don't get to pick.

Deep focus, which puts foreground, middleground, and background into equally sharp and precise perspective, is the only choice on the table now.

- The foreground is defined forcefully. Like a Sorcerer's Apprentice nightmare come-to-life, it takes the form of 8-foot by 8-foot by 40-foot, welded, corrugated stackable, color-coded, steel containers, bobbing, sitting, treading time away in traffic-jammed harbors, portsides, railyards, and other limbos of neither here-nor-there, everywhere containing precious cargo of critical pieces and parts of the 18,000-piece wonders each new 2,200 square foot home becomes.

- The middleground, both bristling with menace and shimmering with opportunity and reward, is land, or more precisely, vacant developed home sites. There don't appear to be enough of them, and too many people and firms and dollars want them, and the spigots controlling their supply – sellers and regulators – are out of buyers' realm of predictability and control.

- The background – perhaps the biggest and most consequential riddle – pronounced itself with the arrival, devastation, and lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Its barbell-shaped form is simple: Home on one side, Work on the other.

The rest is, well, complicated.

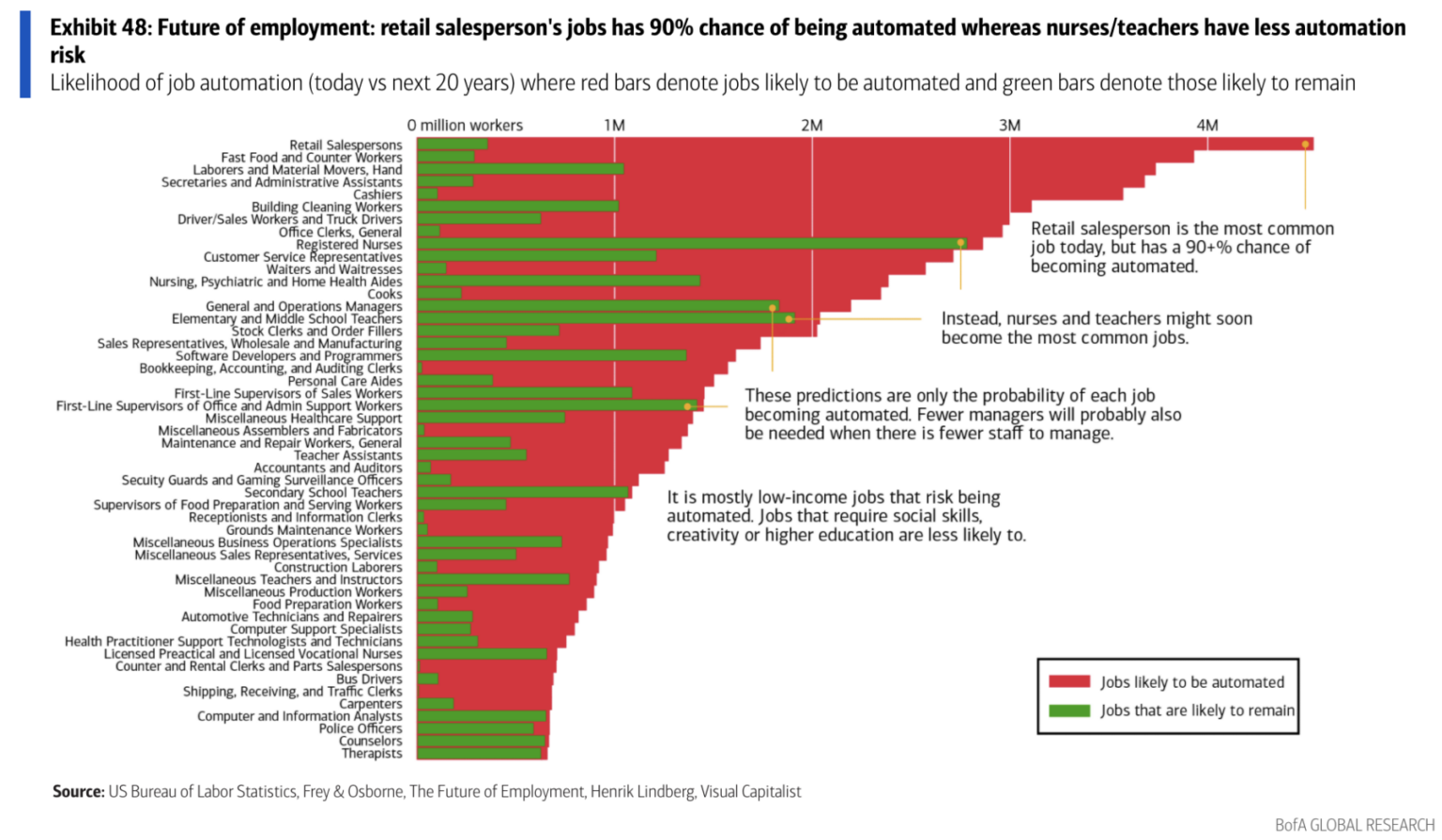

Consider the "Work" end of the barbell for a moment. In a Big Picture blog analysis, Barry Ritholtz – crediting a chart from Bank of America managing director of research Haim Israel -- helps us visualize the past's collision with the future of work in red and green here.

The red – for those, like me, whose eyesight may be challenged – stands for jobs that are bound, sooner than later, to be automated, roboticized, eliminated by advancing machine learning or technological capability. The Ritholtz punch-line in the day 2 analysis of this past Friday's employment report is right here:

Have a look at the chart from Bank of America’s Haim Israel. Automation is inexorably driving huge numbers of jobs away. I suspect workers have figured for themselves they want to skip taking positions that will eventually be automated anyway. As we discussed back in July, the CARES Act monies flowed to people who recognized this — and so they learned new skills, got degrees online, trained themselves for new careers."

These days, the labor market is even more unusually dynamic than typical. It is not an exaggeration to suggest it is in the midst of a radical transformation."

Ritholtz' parting take-away nugget is that economists can scarcely be expected to predict what they do not understand to begin with.

Now, let's swing over to the other pole of the Home-Work barbell.

Home.

Take a quick look at this piece on the pandemic's immediate and near-term aftermath impacts on housing, generated last week by Earlene K.P. Dowell, a program analyst in the Census Bureau’s Economic Management Division. The analysis pairs Census Bureau data with Zillow data analysts, crunching an array of Census and other U.S. agency reports. A few highlights:

demand boomed in more affordable urban areas.

In 20 of the top 35 largest markets, over half of urban workers were reverse commuters.

The mass shift to remote work — even part-time — is now another factor

A major bump up in pending home sales in vacation destinations was predictable

One more macro issue – all about home – has surfaced as the decade's defining social and demographic traits reveal themselves:

A new Pew Research Center analysis of census data finds that in 2019, roughly four-in-ten adults ages 25 to 54 (38%) were unpartnered – that is, neither married nor living with a partner.1 This share is up sharply from 29% in 1990.2 Men are now more likely than women to be unpartnered, which wasn’t the case 30 years ago."

This factor will surely impact what economists, experts, and analysts currently debate as a fundamental indicator in housing supply and demand. Already, the math of household income and wealth correlated with the household composition has begun to alter the calculus of household formation's impact on new-home demand.

Looking across a range of measures of economic and social status, unpartnered adults generally have different – often worse – outcomes than those who are married or cohabiting.

Now, where our own particular analysis heads from here is to a non-complicated conclusion:

Homebuilding's business leaders, and their partners' strategic leadership, and their investors' leadership, as well, stand in the throes, now, of difficult, sometimes-conflicting, priorities. These priorities make mincemeat of linear, critical path tactics, and call for multi-dimensional, simultaneous, critical system strategy, management, and responsibility and accountability.

Getting through today may have more to do with those toy-like stacks of shipping containers and what's in them or not. Equally compelling priorities stem from managing team member engagement in a context that presents – each passing day – a new emergent challenge. Team members, already running on fumes and adrenaline to keep coming up with the latest day's workarounds, are an organization's front-line, and many have toiled the past several months in a "reality distortion-field" environment. What happens with them, for them, and to them in the weeks ahead may set the tone for what a homebuilding enterprise will or will not be able to accomplish in 2022 and beyond.

Here's an uncannily appropriate case example of the kind of instance where a leader's presence and messaging could tap into to strengthen engagement with those critical front-liners before it's too late:

A few years ago, I watched the CEO of a public company scream, “I will not accept this forecast!” at the president of one of his divisions, laced with some angry profanity. In the days that followed, the CEO and division president went back and forth, revising the revenue projections upward to more “acceptable” results, until the CEO finally OK’ed the next quarter’s forecast. While the numbers looked better on paper, they were not based on any real progress with customers or any reality within the business.

Fast forward to the end of quarter. The CEO was furious because the revenue numbers didn’t match the revised and more acceptable (to him) forecast. Ironically, the results were exactly on track with the initial forecast. As a result, the CEO abruptly initiated a round of layoffs and cut important internal investments to help the business operate more efficiently with customers. The numbers were telling the true story from the beginning, but the CEO wouldn’t accept and act on a reality he didn’t like. This created an avalanche of problems for employees and customers that negatively impacted future value of the business.

If this scenario even vaguely resembles anything going on among homebuilding firms and their partners' organizations now – and word is, variations on this theme have occurred and continue to happen – have a look at an alternative way to keep the foreground, middleground, and background in better balance. Check out this link.

You don't have to give up being results-focused to accept reality. In an environment such as the one we're in, accepting reality and instilling trust may be your best option to achieve those results at the end of the day.