Land

Drought Shifts Wildfire's Fault Lines Into No Man's Land Buys

Arguments pro and con on the risks of development, where and where not to develop, who's got which rights to do what, etc., are the matters of power, money, and politics. Meanwhile, there's a housing affordability crisis.

Millions of acres of scorched earth, tens of thousands of homeless people living in the streets, and hundreds of thousands more barely making ends meet to put a roof over their heads.

It sounds biblical, but it's here, now. And it's housing, where the first-best option to make homes and communities more affordable is to build them farther from central cities where the land is cheaper looks to have come to a violent head with nature.

Arguments pro and con on the risks and threats of development, where and where not to develop, what the law says, what the insurance companies will say, who's got which rights to do what, etc., are the matters of power, money, and politics playing out in the cauldron of a housing affordability crisis.

Nature, however, scoffs at such dynamics, and does what it will do. Who's voted in or out; who wins what lawsuit, who gains what approvals to do what can legally be done on what property – these things matter little in a world where fire itself is moving the fault lines.

The situation – for humans – amounts to a wretched debate: climate sanity versus housing affordability and access. This issue will not be solved in 2021. Instead, another tally, another death count, another statistical print-out of another year's toll, while a debate continues on the false equivalency that a smarter response on building and development's part to fueling Mother Nature's wrath is the same as being against more affordable housing.

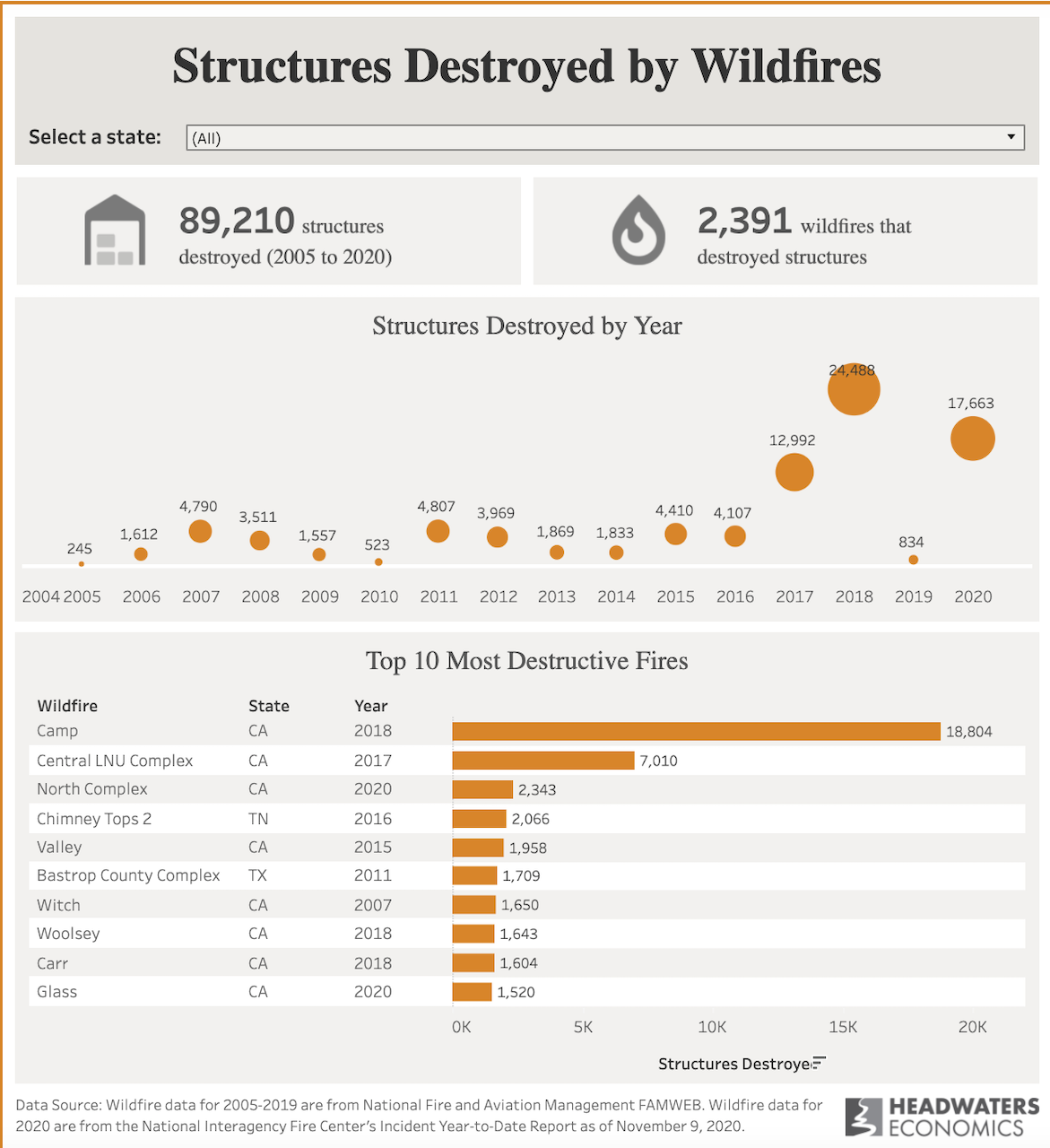

Fifty-five hundred square miles – roughly the size of Connecticut – burned in California's 2020 wildfires, which destroyed 10,500 structures and killed 33 people. In 2020, wildfires in the U.S. numbered 58,950, a 17% increase from the prior year, and scorched 10.1 million acres, more than double 2019.

And this year, early yet for the onset of 2021's barrage, has the makings to be worse, far worse.

This year’s wildfire season is predicted to be another severe one. From January 1 to June 8, 2021 there were about 26,700 wildfires, compared with 20,216 in the same period 2020, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. About 792,000 acres were burned, compared with 558,724 in 2020. On June 8, 10 states reported active large fires including Arizona which had four fires burning. The Telegraph fire has been burning since June 4 and has destroyed 71,756 acres in Pinal County, according to Arizona Interagency Wildfire Prevention. The Mezcal fire burned 65,825 acres since it started on June 1 in Gila County and was 23 percent contained on June 8.

Warning after warning after warning – they either fall on deaf ears or skip, annoyingly like a broken-record.

The science of aridity, and the science of heat, and the science of fuel and the science of the daisy chain of all of these things occurring at once, in connection to one another, add up to humans trying to get their heads around what's at risk. Here's how that reads in a series of articles that emerged in recent days.

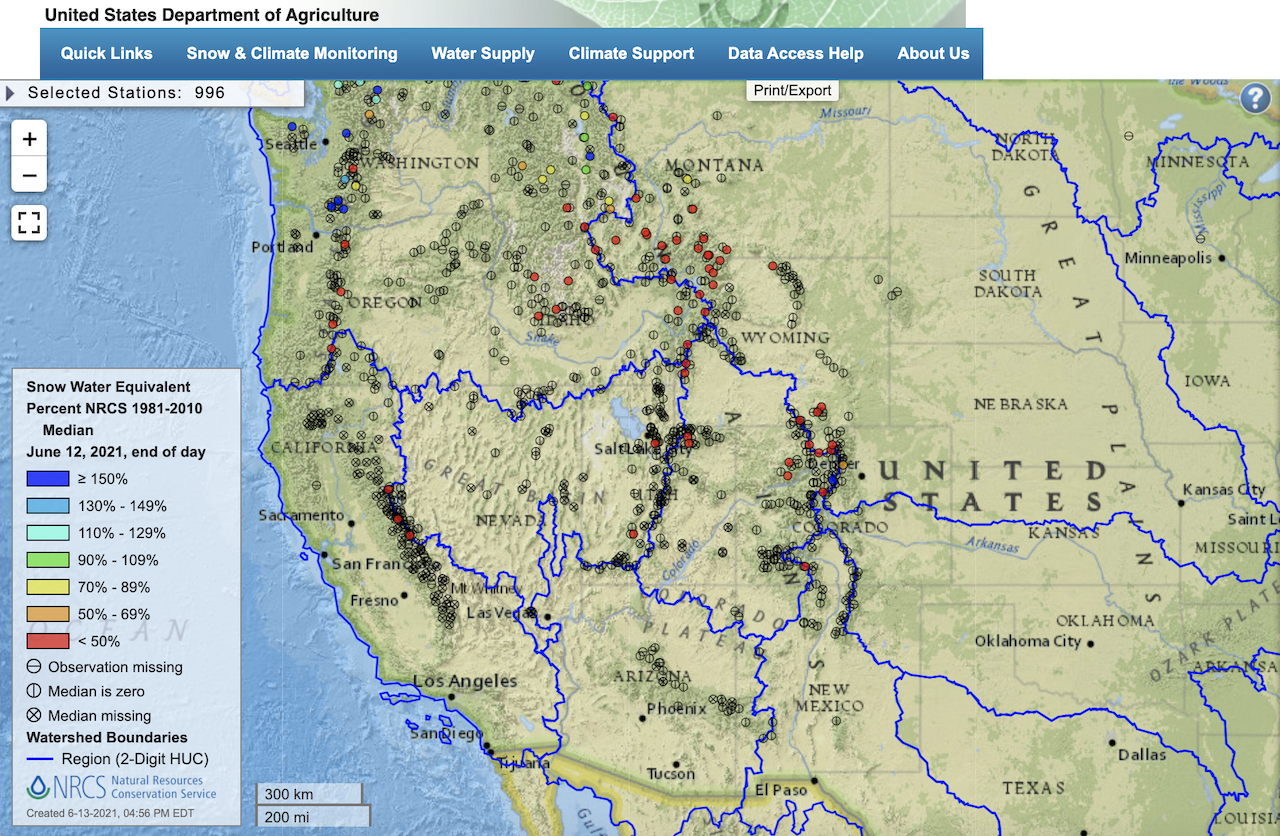

The New York Times' Nadja Popovich – with extensive visualization and mapping from the Times' graphics staff – lays out a rich geographical discovery of where threats are greatest and why, mostly to do with a longstanding lack of snow and rain.

Popovich writes that risks are not just of deadly fires, but areas running short of water:

Usually, melting mountain snowpack helps to replenish reservoirs, rivers and soils throughout the spring and summer. (You can think of snowpack as a sort of natural reservoir system that releases water over time.)

But in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California and other parts of the lower West, snowpack melted early this year because of higher spring temperatures and other unfavorable conditions. Much of the runoff didn’t make it to reservoirs and streams at all because already-parched soils sucked up the water.

The Washington Post's Diana Leonard explores the convergence of an old drought and a new moving-target array of potential igniters in her piece, "Intensifying California drought promises ‘very concerning’ fire season."

The National Interagency Fire Center’s outlook shows above-normal fire potential for much of the West, as well as the northern plains, given widespread drought in addition to the expected warmer and drier-than-normal conditions this summer.

Extreme heat is already overlapping with drought in Western and northern tier states. California, Oregon, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming and North Dakota all saw record-breaking high temperatures in early June, and all are now regions of expanding and intensifying drought.

Yahoo's Ben Kesslen reports on how the western region as a whole is historically dry, to the degree that the question arises as to how to accurately describe the condition of aridity:

This year's aridity is happening against the backdrop of a 20-year-long drought. The past two decades have been the driest or the second driest in the last 1,200 years in the West, posing existential questions about how to secure a livable future in the region.

It's time to ask, "Is this a drought, or is it just the way the hydrology of the Colorado River is going to be?" said John Entsminger, the general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

In a photo-filled essay The Atlantic's Alan Taylor offers grim glimpses of human, animal, and earth in distress and at existential risk, while Los Angeles Times writer Alex Wigglesworth delimbs evidence from all theoretical and practical sides of the the issue, letting audiences come to their own conclusion as to what they'll expect, and how they'll respond or react.

Although the scope of last year’s storms was unusual, lightning itself is not uncommon during California summers. Lightning can result from the North American monsoon, which develops in late June as moist air from Mexico moves toward Arizona and New Mexico in July, or from tropical storms that travel up the coast in late summer to early fall, Hockenberry said.

“So we are expecting lightning events,” he said. “But what we can’t predict is exactly where they’re going to be and how widespread.”

What builders and developers and investors do will likely follow the arc of policy, legality, and household preference, all of which operate with manifest indifference to the shift in wildfire's fault lines.

An unfortunate, unproductive, and unhelpful binary dispute, i.e. "if you oppose sprawling development, you oppose housing for people who need it" – sits in the way of better, more intelligent, and potentially more valued solutions.

A starting place for a fruitful, evidence-based solutions approach to balancing the crisis need for more housing for more people with the dangers of building into the teeth of potentially catastrophic loss from wildfires and water shortages might be here. Simply take a look at the number of structures lost to wildfires, and resolve to zero that number out in as short a time as possible.