Land

Drive 'Til You Qualify Gets A Work-From-Anywhere Makeover

How powerfully will the blended allure of desirably-priced housing and liberation from a daily commute move people to move, predictably?

With heightened stakes on getting it correct, or losing a lot, homebuilders' Jeopardy response keeps being roughly this.

"What is the housing market in a work-from-anywhere near-, mid-, and long-term future?"

The clue being, "Matching people who want to buy a home to places where their payment power is enough."

Will running out of attainably priced housing options where people currently live and work force a great rotation from expensive market metros to less pricey second and third tier markets?

Will constraint act as a societal catalyst?

Will that rotation get a big timely assist from leverage talented workers may wrest in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling them to work-from-anywhere, namely home, in a housing market more suitable to their pocketbooks?

That construct tempts embrace.

It would conveniently align where it is less expensive to invest, develop, and build new homes with where people might prefer to settle and ground their families were they untethered from having to show up five days a week for an 8-hour-or-so day at the office.

That construct would posit that the blended allure of desirably-priced housing and liberation from a daily commute would move people to move, predictably.

That construct underlies the reporting here, by New York Times staffers Conor Dougherty and Ben Casselman. The article observes that would-be homeowners – many of them biological-clock-driven millennials late to the family-formation game – are stretching boundaries once centripetally governed by downtown job centers. Dougherty and Casselman write:

The pandemic may have upended that economic order, in California and elsewhere. Thousands of families that could afford to do so fled cities last spring, and while some will return, others will not — particularly if they are able to continue to work remotely at least part of the time. One recent study estimated that after the pandemic, one-fifth of workdays would be “supplied remotely” — down from half during the height of the pandemic but far above the 5 percent before it.

If those trends hold, it will make it easier for many workers to live not just in farther-out towns like Lathrop but to abandon high-cost regions like the Bay Area altogether. Midsize cities that for years have tried — usually in vain — to recruit large employers through tax breaks can now attract workers directly.

“If Google moves to Cleveland, that’s great, but if one Googler moves to Cleveland, that’s also great,” said Adam Ozimek, chief economist of Upwork, a freelancing platform.

To some extent, the pandemic accelerated a shift that was already taking place. When the housing bubble burst, members of the millennial generation were in their teens and 20s. Now the oldest of them are turning 40, and about half are married. They are hitting the milestones when Americans have traditionally moved to the suburbs.

Still, the blind spot we all have to admit is this. Work from anywhere may or may not be a thing. Moreover, even if it is a thing, the operative term in the expression is "work," and questions as to what that will be and what it will mean remain open.

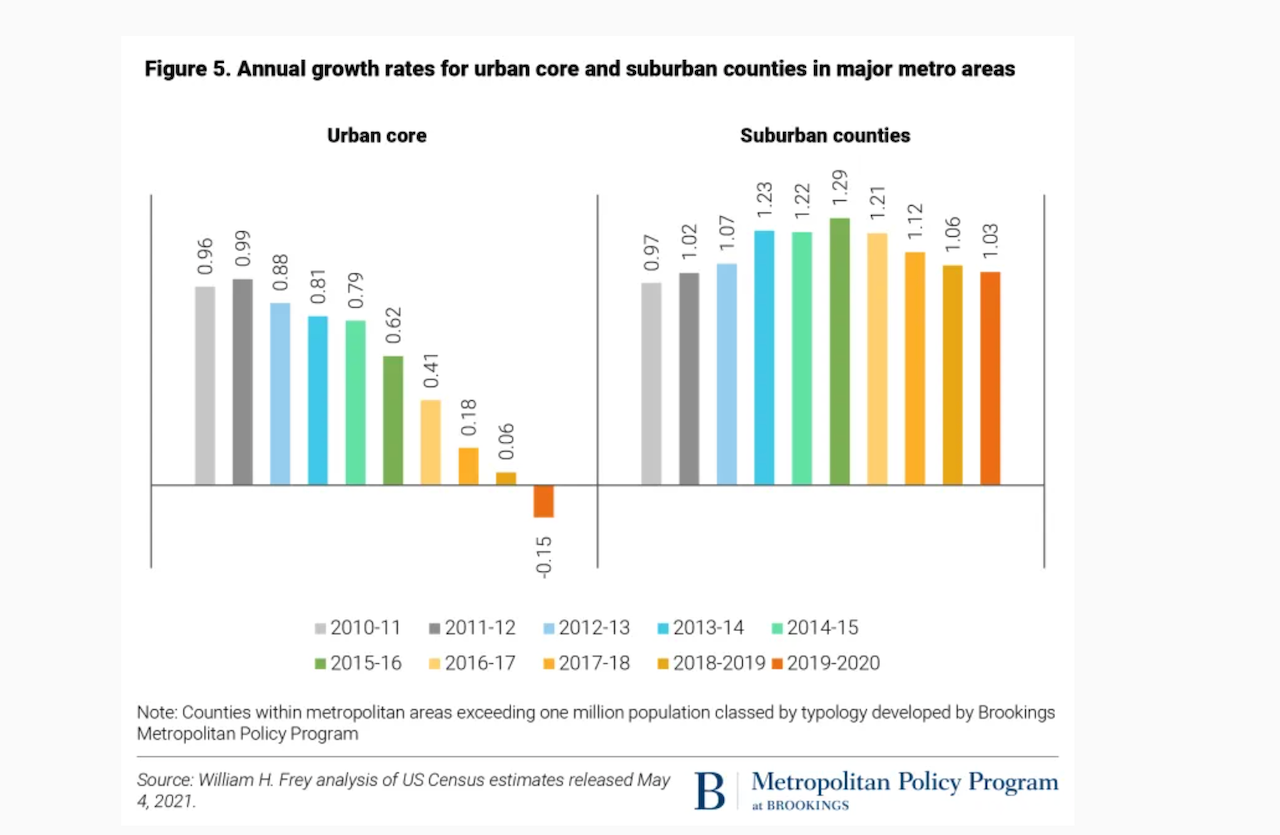

First, new migration trends, Brookings Institution fellow William Frey notes, are hard to decipher much before they've already happened and clearly pronounced themselves.

It is difficult to predict how urban populations will fare in the post-pandemic era, say two to five years down the road. It is most likely that natural increase levels will pick up as pandemic-related deaths subside, and couples will resume something closer to pre-pandemic childbearing patterns. It is also possible—and quite likely—that the recent restrictive immigration policies will be reversed, as there becomes a greater awareness of the important role that immigration plays in bolstering the nation’s overall growth, especially among its younger labor force population.

As to domestic migration, there are real questions about how much the mid-2010s dispersal to suburbs and smaller areas will continue, and whether the selective “flight from density” in the past year will become a way of life after cities become safer, and more jobs become available there. There is some likelihood that the latter “flight” could be short lived or even reversed since much of it may have been temporary in nature. This could change as new generations of young people—a traditional source of big city growth—will once again find places like Manhattan and San Francisco attractive. These are questions that cannot yet be answered.

Second, out-migration from dense urban downtowns is one thing, and in-migration to housing markets and submarkets that are attractive as places to live and affordable is another.

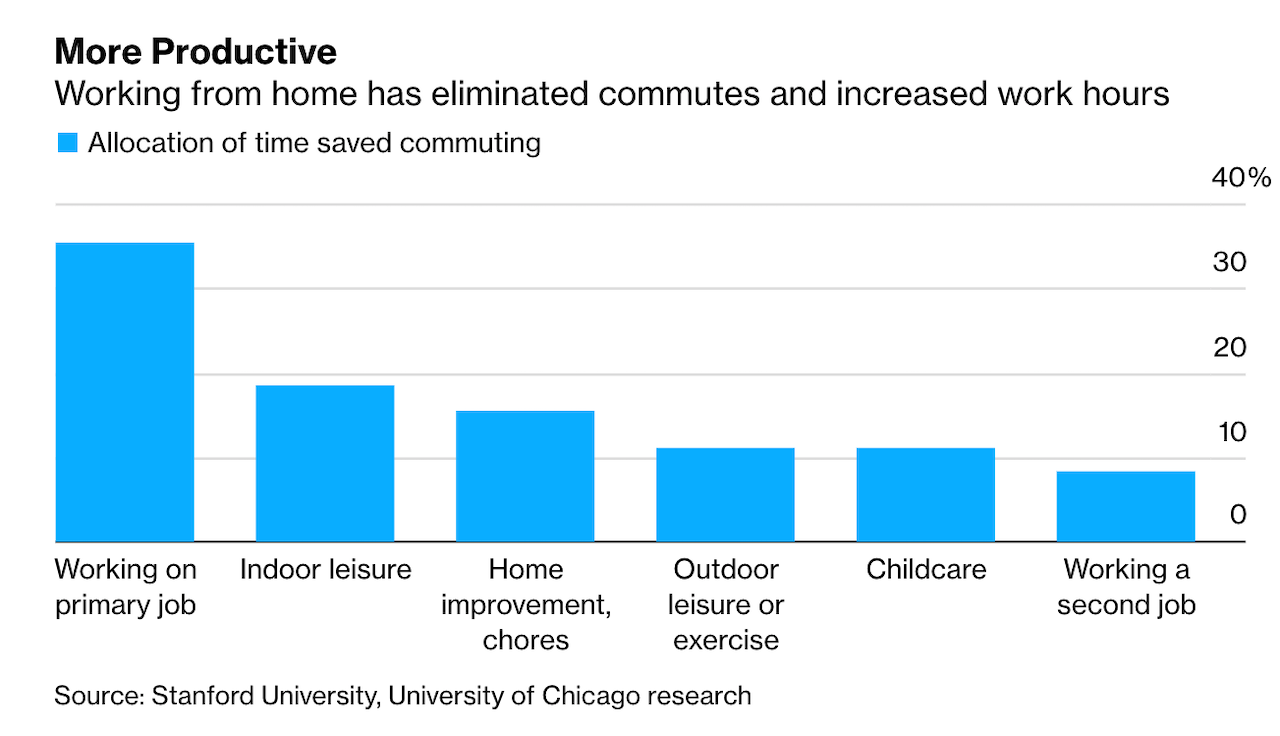

This piece, "Americans Are Done With 5-Days A Week in the Office. Here's What That Means for the Economy," based on Bloomberg correspondent Olivia Rockeman's interview with Stanford University economist Nicholas Bloom, suggests a geographical gap between WFH and WFA. Bloom's theory is that, to some extent, there's no going back to pre-pandemic practices of 5-days-a-week commutes to workplaces for all employees, especially in light of productivity data that came to light during stay-at-home periods. Without commutes, many workers got more done.

Hybrid – a remote and office mix across a 5-day week – may mean the distance between job center and home can stretch by some measure. But will it be so elastic as to enable the working household to drive until they qualify for a mortgage loan-to-income they can afford?

Stanford's Bloom says:

We call it the “Donut Effect.” The places losing the most people are centers of big cities. Downtowns are doing very badly, they’ve lost roughly 15% of people and businesses, and the suburbs of the same large cities are doing really well. In fact, it looks like the suburbs of large cities are the hottest property markets. We think that this is all due to the move to hybrid. If you can work from home two days a week, it makes it more appealing to live in the suburbs because you have to commute less. But it makes it impossible to go and move to Alaska, it doesn’t work.

Third, residential developers, investors, and builders should remember how humbling their path-of-growth models of a little over a decade ago worked out to be. Those roadmaps, based on "real demand" – demographics, job formations, household formations, and family formations, plus solid corporate earnings, of the 2003-to-2007 housing economy – exposed the risks in overinvesting in trends that seemed logical and rational.

That they were fueled by illogical and irrational financial mechanisms seemed beside the point at the time. One could say that now, in an economy buoyed more by Central Bank largesse than it ever has been before, there's some irrationality around to spare.